Reducing body fat safely and effectively requires understanding the science behind fat metabolism and implementing evidence-based lifestyle changes. Whilst many seek rapid results, sustainable fat loss typically occurs at 0.5–1 kg weekly through a combination of dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural strategies. Excess body fat, particularly visceral fat, increases risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic complications. This article examines clinically proven methods for fat reduction, nutritional strategies, exercise recommendations, and when to seek medical guidance for weight management.

Quick Answer: Safe, sustainable body fat reduction occurs at 0.5–1 kg weekly through creating a calorie deficit via dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural changes, as recommended by NHS and NICE guidance.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

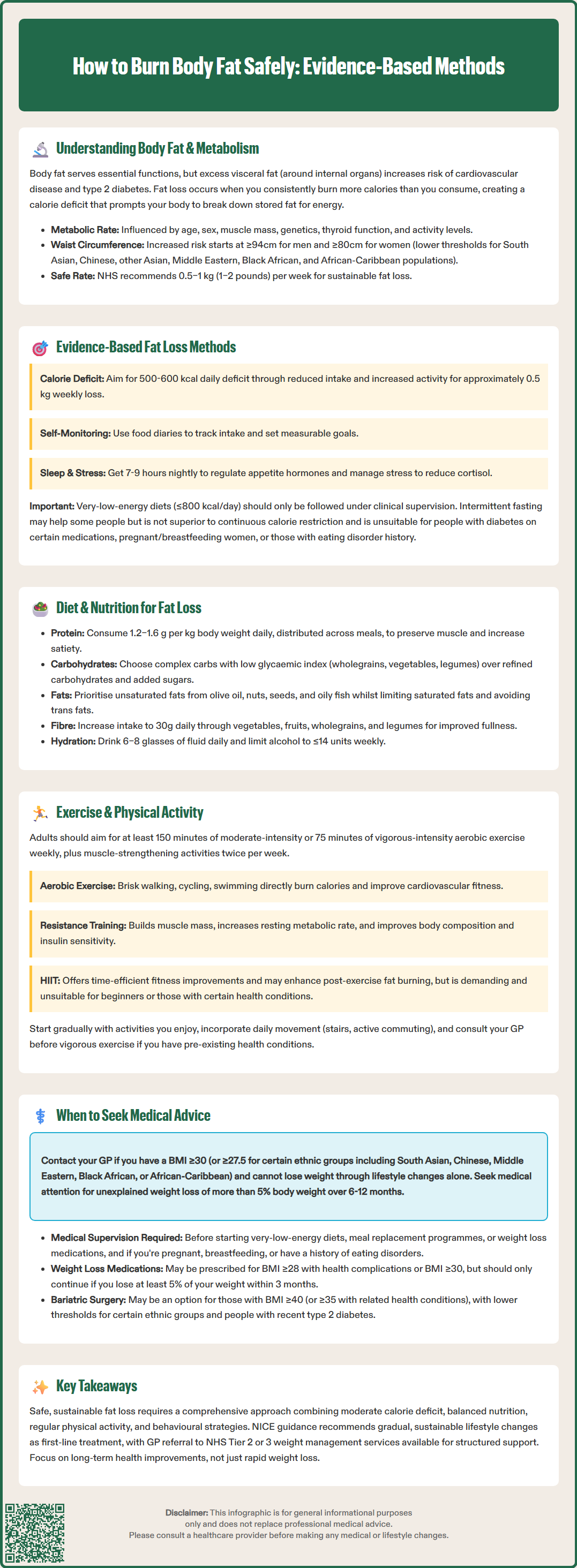

Start HereBody fat, or adipose tissue, serves essential physiological functions including energy storage, hormone production, and thermal insulation. However, excess body fat—particularly visceral fat surrounding internal organs—is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic conditions. Understanding how the body stores and utilises fat is fundamental to achieving sustainable fat loss.

Metabolism refers to the biochemical processes that convert food into energy. Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) represents the energy expended at rest to maintain vital functions such as breathing, circulation, and cell production. Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) includes BMR plus energy used during physical activity and food digestion (thermic effect of food). Fat loss occurs when energy expenditure consistently exceeds energy intake, creating a calorie deficit that prompts the body to mobilise stored fat for fuel.

The process of fat oxidation (fat burning) involves breaking down triglycerides stored in adipocytes into fatty acids and glycerol, which are then transported to tissues and oxidised for energy. This process is regulated by hormones including insulin, glucagon, cortisol, and catecholamines. Factors affecting metabolic rate include age, sex, body composition, genetics, thyroid function, and activity levels. Men typically have higher metabolic rates due to greater muscle mass, whilst metabolic rate tends to change with age largely due to changes in body composition (particularly loss of fat-free mass) and individual factors.

Waist circumference is an important additional risk marker alongside BMI, with NHS guidance suggesting increased risk at ≥94cm for men and ≥80cm for women (with lower thresholds for people of South Asian, Chinese, other Asian, Middle Eastern, Black African, or African-Caribbean family origin).

It is important to recognise that "fast" fat loss claims should be approached cautiously. Rapid weight loss often involves water and muscle loss rather than fat, and extreme approaches may be unsustainable or medically inadvisable. The NHS recommends a gradual weight loss of 0.5–1 kg (1–2 pounds) per week as safe and sustainable for most individuals.

Sustainable fat reduction requires a multifaceted approach combining dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural changes. NICE guidance (CG189) recommends a comprehensive lifestyle intervention as first-line management for overweight and obesity, emphasising gradual, sustainable changes rather than extreme restriction.

Creating a calorie deficit remains the cornerstone of fat loss. A deficit of 500–600 kcal per day typically produces weight loss of approximately 0.5 kg weekly. This can be achieved through reduced calorie intake, increased energy expenditure, or—most effectively—a combination of both. Low-energy diets (800–1,600 kcal/day) and very-low-energy diets (≤800 kcal/day) should only be followed with clinical supervision and as part of a multicomponent programme, in line with NICE guidance.

Behavioural strategies supported by evidence include:

Self-monitoring through food diaries or mobile applications

Setting specific, measurable, achievable goals

Identifying and modifying environmental triggers for overeating

Developing stress management techniques (as stress elevates cortisol, which may promote abdominal fat storage)

Ensuring adequate sleep (7–9 hours nightly), as sleep deprivation disrupts appetite-regulating hormones

Intermittent fasting approaches, such as time-restricted eating or the 5:2 diet, have gained attention. Whilst some evidence suggests these may facilitate calorie restriction and improve metabolic markers, there is no conclusive evidence they are superior to continuous calorie restriction for fat loss. Individual response varies considerably, and these approaches are not suitable for everyone, particularly those with diabetes on insulin or sulfonylureas, pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with a history of eating disorders, or certain other medical conditions.

Commercial weight loss programmes with evidence of effectiveness include those offering structured support, regular monitoring, and gradual dietary changes. The NHS provides access to various weight management services, and your GP can advise on locally available Tier 2 or Tier 3 programmes.

Nutritional composition significantly influences satiety, metabolic health, and adherence to dietary changes. Whilst various dietary approaches can facilitate fat loss, the optimal diet is one that creates a sustainable calorie deficit whilst meeting nutritional requirements.

Macronutrient considerations include:

Protein: Adequate protein intake (1.2–1.6 g per kg body weight daily) supports muscle preservation during weight loss, enhances satiety, and has a higher thermic effect than carbohydrates or fats. Good sources include lean meats, fish, eggs, legumes, and dairy products. Protein should be distributed across meals to optimise muscle protein synthesis. People with kidney disease should consult their GP or a dietitian before increasing protein intake.

Carbohydrates: Focus on complex carbohydrates with low glycaemic index (GI) values—such as wholegrains, vegetables, and legumes—which provide sustained energy and promote satiety. Refined carbohydrates and added sugars should be minimised as they provide calories with limited nutritional value and may promote insulin spikes followed by hunger.

Fats: Whilst energy-dense (9 kcal per gram), dietary fats are essential for hormone production and nutrient absorption. Emphasise unsaturated fats from sources like olive oil, nuts, seeds, and oily fish, whilst limiting saturated fats and avoiding trans fats.

Practical dietary strategies include:

Increasing fibre intake (30g daily) through vegetables, fruits, wholegrains, and legumes to enhance satiety and digestive health

Maintaining adequate hydration (6–8 glasses of fluid daily); thirst is sometimes mistaken for hunger

Practising portion control using smaller plates and mindful eating techniques

Reducing alcohol consumption, following UK low-risk drinking guidance (≤14 units/week, spread across several days with drink-free days)

Planning meals and preparing food at home to control ingredients and portions

The NHS Eatwell Guide provides a framework for a balanced, sustainable dietary pattern. Very-low-energy diets (≤800 kcal/day) or meal replacement programmes may be appropriate for some individuals with obesity under medical supervision, but are not suitable for everyone, should be time-limited, and require careful monitoring.

Physical activity is crucial for fat loss, metabolic health, and weight maintenance. Exercise increases energy expenditure, preserves lean muscle mass during calorie restriction, and improves cardiovascular and metabolic health markers. The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend adults undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly, plus muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days. Breaking up sedentary time and including balance exercises (especially for older adults) are also recommended.

Aerobic exercise (cardiovascular activity) directly increases calorie expenditure and improves cardiovascular fitness. Moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or dancing—activities that elevate heart rate and breathing but allow conversation. Vigorous activities include running, fast cycling, or aerobic classes. For fat loss, longer duration moderate-intensity exercise may be particularly effective, as fat oxidation increases during sustained activity.

Resistance training (strength training) is equally important. Building and maintaining muscle mass can modestly increase resting metabolic rate and improves body composition and insulin sensitivity. Exercises should target major muscle groups using bodyweight, resistance bands, free weights, or machines. Beginners should start with lighter weights and focus on proper technique.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) involves short bursts of intense activity alternated with recovery periods. Evidence suggests HIIT can be time-efficient for improving fitness and may enhance fat oxidation post-exercise, though this effect (excess post-exercise oxygen consumption or EPOC) contributes modestly to overall energy expenditure. HIIT is demanding and may not suit everyone, particularly those new to exercise or with certain health conditions.

Practical recommendations:

Start gradually if currently inactive, progressively increasing duration and intensity

Choose activities you enjoy to enhance adherence

Incorporate movement throughout the day (active commuting, taking stairs, standing breaks)

Consider working with a qualified fitness professional to develop a personalised programme

Individuals with pre-existing health conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease, should consult their GP before commencing vigorous exercise programmes.

Whilst lifestyle modification is appropriate for most individuals seeking fat loss, certain circumstances warrant medical consultation. Contact your GP if:

You have a BMI ≥30 kg/m² (or ≥27.5 kg/m² for people of South Asian, Chinese, other Asian, Middle Eastern, Black African, or African-Caribbean family origin) and have been unable to lose weight through lifestyle changes alone

You have obesity-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnoea, or cardiovascular disease requiring coordinated management

You experience unexplained weight loss (losing >5% body weight over 6–12 months without trying), which may indicate underlying medical conditions including thyroid disorders, diabetes, malignancy, or gastrointestinal disease

You have symptoms suggesting metabolic or endocrine disorders: persistent fatigue, cold intolerance, hair loss, or menstrual irregularities

You are considering very-low-energy diets, meal replacement programmes, or weight loss medications, which require medical supervision

You have a history of eating disorders or develop concerning eating behaviours

You are pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning pregnancy

You take medications that may affect weight or interact with dietary changes

You have urgent red flags such as GI bleeding, persistent dysphagia, unexplained cough/haemoptysis, or palpable masses

Medical weight management options your GP may discuss include:

Pharmacological interventions: Medications such as orlistat (available over-the-counter at 60mg or on prescription at 120mg) may be considered for individuals with BMI ≥28 kg/m² with comorbidities or BMI ≥30 kg/m². Orlistat should be used as part of a multicomponent plan and continued only if ≥5% weight loss is achieved at 3 months, with regular review. GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide) may be prescribed within specialist weight management services for specific indications, with defined time limits and stop rules.

Specialist referral: Tier 3 weight management services provide multidisciplinary support for complex obesity. Bariatric surgery may be considered for individuals with BMI ≥40 kg/m² (or ≥35 kg/m² with comorbidities), with consideration for people with recent-onset type 2 diabetes at BMI 30–34.9 kg/m². Lower BMI thresholds apply for certain ethnic groups.

Psychological support: If emotional eating, binge eating, or psychological barriers impede progress, referral to psychological services may be beneficial.

Remember that sustainable fat loss is a gradual process requiring patience and consistency. Extreme approaches promising rapid results are rarely sustainable and may compromise health.

The NHS recommends gradual weight loss of 0.5–1 kg (1–2 pounds) per week as safe and sustainable for most individuals. Rapid weight loss often involves water and muscle loss rather than fat and may be medically inadvisable.

Whilst fat loss can occur through dietary changes alone, exercise is crucial for preserving muscle mass, increasing energy expenditure, and improving metabolic health. UK guidance recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly plus resistance training.

Consult your GP if you have BMI ≥30 kg/m² with unsuccessful lifestyle changes, obesity-related conditions like type 2 diabetes, unexplained weight loss, or are considering medical weight management options such as prescription medications or specialist referral.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.