Ozempic (semaglutide) is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist licensed in the UK for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Insulin resistance—a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin—is a key driver of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. By enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon, slowing gastric emptying, and promoting weight loss, Ozempic addresses multiple mechanisms underlying insulin resistance. This article examines how Ozempic improves insulin sensitivity, reviews clinical evidence, discusses who may benefit, and outlines safety considerations alongside alternative management strategies.

Quick Answer: Ozempic (semaglutide) improves insulin resistance primarily through weight reduction, enhanced glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressed glucagon release, and slowed gastric emptying in adults with type 2 diabetes.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

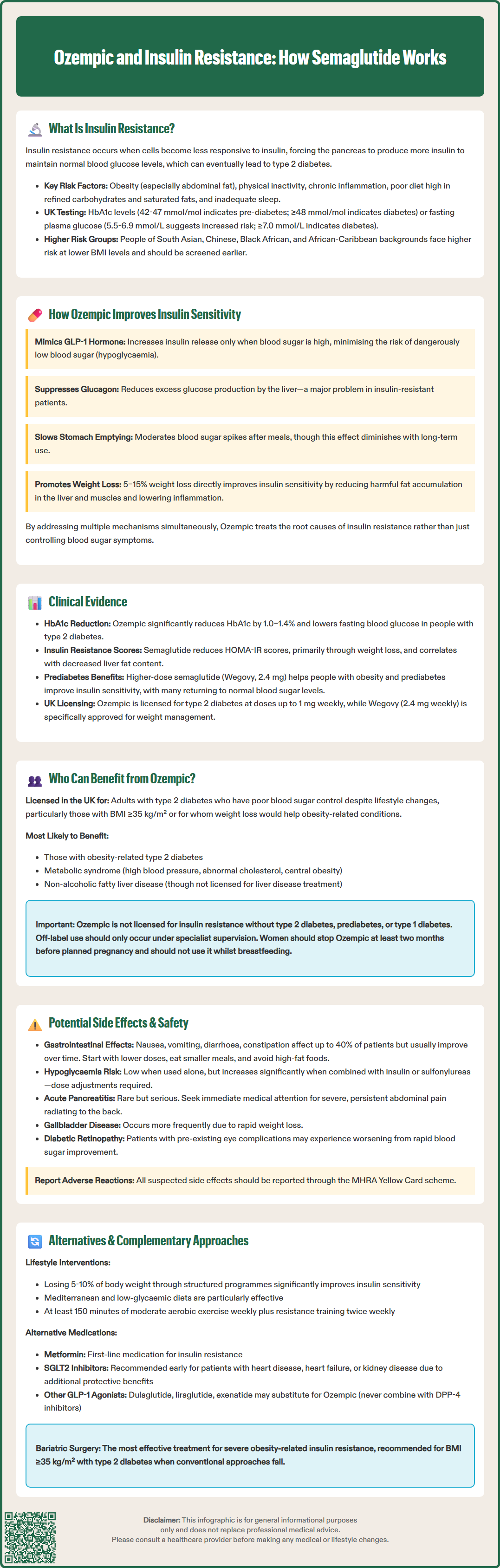

Start HereInsulin resistance is a metabolic condition in which the body's cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin, which is produced by the pancreas. Insulin normally facilitates the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where it is used for energy. When cells resist insulin's signals, the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels. Over time, this compensatory mechanism can become insufficient, leading to elevated blood glucose and potentially progressing to type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Several factors contribute to the development of insulin resistance. Obesity, particularly excess visceral adipose tissue around abdominal organs, is strongly associated with reduced insulin sensitivity. Adipose tissue releases inflammatory cytokines and free fatty acids that interfere with insulin signalling pathways. Physical inactivity further compounds the problem, as regular exercise enhances glucose uptake by skeletal muscle independently of insulin. Genetic predisposition also plays a role, with certain populations demonstrating higher susceptibility.

Other contributing factors include chronic inflammation, hormonal imbalances (such as polycystic ovary syndrome), certain medications (including corticosteroids), and ageing. Poor dietary habits—especially diets high in refined carbohydrates and saturated fats—can exacerbate insulin resistance. Sleep deprivation and chronic stress, which elevate cortisol levels, may also impair insulin sensitivity.

Insulin resistance often exists as part of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance. Early identification through testing is important, as insulin resistance is largely asymptomatic until complications develop. In the UK, testing typically involves measuring HbA1c (42-47 mmol/mol indicates non-diabetic hyperglycaemia) or fasting plasma glucose (5.5-6.9 mmol/L suggests increased risk). Diabetes is diagnosed at HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol or fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L. People from South Asian, Chinese, Black African and African-Caribbean backgrounds are at higher risk at lower BMI thresholds.

Urgent medical assessment should be sought for marked hyperglycaemia with weight loss, ketones, dehydration or acute illness. Addressing modifiable risk factors remains the cornerstone of prevention and management.

Ozempic (semaglutide) is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) licensed in the UK for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. It mimics the action of endogenous GLP-1, an incretin hormone released by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake. By binding to GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic beta cells, semaglutide enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion—meaning insulin is released only when blood glucose levels are elevated, thereby reducing the risk of hypoglycaemia.

Beyond its direct effects on insulin secretion, Ozempic influences insulin resistance through several mechanisms. The medication suppresses glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, which reduces hepatic glucose production. This is particularly relevant in insulin-resistant states, where excessive glucagon contributes to hyperglycaemia. Semaglutide also slows gastric emptying, which moderates postprandial glucose excursions and reduces the insulin demand placed on already resistant tissues. It should be noted that this gastric emptying effect tends to attenuate with chronic therapy, as documented in the MHRA Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC).

A key mechanism by which Ozempic improves insulin sensitivity is through weight reduction. Clinical trials have demonstrated substantial weight loss with semaglutide therapy, often in the range of 5–15% of body weight. As visceral adiposity decreases, inflammatory markers decline and insulin signalling pathways become more responsive. Weight loss also reduces lipotoxicity—the harmful accumulation of lipids in non-adipose tissues such as liver and muscle—which directly impairs insulin action.

Some research suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists may have effects on adipose tissue metabolism and adipokine profiles, though these findings remain preliminary and require further investigation. The multifaceted actions of semaglutide make Ozempic particularly effective in addressing the underlying pathophysiology of insulin resistance, rather than simply managing its glycaemic consequences.

Robust clinical trial data support the efficacy of Ozempic in improving markers of insulin resistance. The SUSTAIN clinical trial programme, which evaluated semaglutide across diverse patient populations with type 2 diabetes, consistently demonstrated significant reductions in HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose—both indirect indicators of improved insulin sensitivity. In SUSTAIN 6, a cardiovascular outcomes trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, semaglutide reduced HbA1c by approximately 1.0–1.4% compared with placebo, with concurrent improvements in body weight.

Assessments of insulin sensitivity have been conducted using homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), a validated surrogate marker. Studies have shown that semaglutide therapy leads to reductions in HOMA-IR scores, though it is important to note that these improvements are largely mediated by weight loss. Research published in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism has demonstrated correlations between improvements in insulin resistance with GLP-1 receptor agonists and reductions in hepatic fat content, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging.

The STEP trials evaluated higher-dose semaglutide (2.4 mg weekly) for weight management. This higher dose is marketed in the UK as Wegovy, distinct from Ozempic which is licensed for type 2 diabetes at lower doses (up to 1 mg weekly). In the STEP programme, participants with obesity and prediabetes experienced substantial improvements in insulin sensitivity markers, with many reverting from impaired glucose tolerance to normoglycaemia. These findings suggest that semaglutide's benefits extend beyond established diabetes to earlier stages of metabolic dysfunction.

Observational data from UK clinical practice supports the trial findings, showing that patients prescribed Ozempic achieve clinically meaningful improvements in glycaemic control and weight. However, it is important to note that individual responses vary, and not all patients experience the same degree of benefit. Long-term data continue to emerge regarding durability of effect and optimal treatment duration.

Ozempic is currently licensed in the UK for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus who have inadequate glycaemic control despite lifestyle modifications, with or without other glucose-lowering medications. According to NICE guidance (NG28), GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide are recommended as second- or third-line therapy, particularly for patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m² (or lower thresholds for people of Black African, African-Caribbean, South Asian, and Chinese family origin) or those for whom insulin therapy would pose significant occupational implications. GLP-1 RAs may also be considered where weight loss would benefit obesity-related comorbidities.

Patients who are most likely to benefit from Ozempic for insulin resistance include those with obesity-related type 2 diabetes, where weight reduction can substantially improve insulin sensitivity. Individuals with evidence of metabolic syndrome—including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and central adiposity—may experience multifaceted benefits beyond glycaemic control. Those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is closely linked to insulin resistance, may also see improvements in hepatic steatosis with semaglutide therapy, although it is important to note that semaglutide is not currently licensed for NAFLD treatment in the UK.

It is important to emphasise that Ozempic is not currently licensed for insulin resistance in the absence of type 2 diabetes, nor for prediabetes, despite promising trial data. Off-label use should be approached cautiously and only under specialist guidance. Patients with type 1 diabetes should not use Ozempic, as it does not replace insulin therapy and has not been studied in this population.

Certain patient groups require careful consideration before initiating treatment. The MHRA SmPC notes that animal studies have shown C-cell tumours in rodents, though the human relevance is uncertain. Patients with severe gastrointestinal disease, including gastroparesis, may not tolerate the medication well. When initiating semaglutide in patients already on insulin, insulin doses should be reduced gradually and carefully to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Renal function should be monitored, particularly in those with pre-existing kidney disease, as gastrointestinal side effects can lead to dehydration and acute kidney injury.

Semaglutide is not recommended during breastfeeding, and should be discontinued at least two months before a planned pregnancy.

The most common adverse effects of Ozempic are gastrointestinal in nature, affecting up to 40% of patients in clinical trials. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. Symptoms are typically most pronounced during dose escalation and often diminish over time as tolerance develops. Starting with a lower dose (0.25 mg weekly) and gradually titrating upwards can help minimise these effects. Patients should be advised to eat smaller, more frequent meals and avoid high-fat foods, which may exacerbate symptoms.

Other common side effects include headache and injection-site reactions such as redness or itching at the injection site.

Hypoglycaemia risk with Ozempic monotherapy is low due to its glucose-dependent mechanism of action. However, when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, the risk increases substantially. Dose adjustments of concomitant medications may be necessary when initiating semaglutide. Patients should be educated about recognising and managing hypoglycaemic episodes, including keeping fast-acting carbohydrates readily available. Those at risk of hypoglycaemia should follow DVLA guidance regarding driving safety.

Rare but serious adverse effects require vigilance. Acute pancreatitis has been reported with GLP-1 receptor agonists, though causality remains debated. Patients should be instructed to seek immediate medical attention if they experience severe, persistent abdominal pain radiating to the back. The MHRA SmPC advises that semaglutide should be stopped if pancreatitis is suspected and not restarted if pancreatitis is confirmed. Gallbladder disease, including cholelithiasis and cholecystitis, occurs more frequently with semaglutide, likely related to rapid weight loss. There have been post-marketing reports of diabetic retinopathy complications, particularly in patients with pre-existing retinopathy who experience rapid glycaemic improvement; ophthalmological monitoring may be warranted in high-risk individuals.

Patients should contact their GP if they experience:

Persistent vomiting or diarrhoea leading to dehydration

Severe abdominal pain

Signs of allergic reaction (rash, difficulty breathing, facial swelling)

Symptoms of pancreatitis or gallbladder disease

Changes in vision

Pregnancy should be avoided during treatment, and semaglutide should be discontinued at least two months before planned conception due to limited safety data.

Suspected adverse reactions should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk or via the Yellow Card app).

Lifestyle modification remains the foundation of insulin resistance management and should be optimised before or alongside pharmacological interventions. Structured weight loss programmes targeting 5–10% body weight reduction can significantly improve insulin sensitivity. The NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme offers evidence-based support for individuals with non-diabetic hyperglycaemia (prediabetes). Dietary approaches emphasising whole grains, lean proteins, vegetables, and healthy fats—whilst limiting refined carbohydrates and processed foods—have demonstrated benefit. Mediterranean and low-glycaemic-index diets show particular promise.

Physical activity is profoundly effective in enhancing insulin sensitivity. NICE recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, combined with resistance training on two or more days. Exercise increases glucose uptake by skeletal muscle through insulin-independent mechanisms and improves body composition. Even modest increases in activity can yield metabolic benefits.

Several alternative pharmacological options exist for managing insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Metformin remains first-line therapy, improving hepatic insulin sensitivity and reducing glucose production. It is generally well-tolerated, though gastrointestinal side effects are common. Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, directly enhances insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue and muscle but carries risks of weight gain, fluid retention, and bone fractures. SGLT2 inhibitors (such as dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) offer complementary mechanisms, promoting urinary glucose excretion and providing cardiovascular and renal benefits. NICE guidance now recommends early consideration of SGLT2 inhibitors for people with established cardiovascular disease, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease.

For patients unable to access or tolerate Ozempic, other GLP-1 receptor agonists may be considered, including dulaglutide, liraglutide, or exenatide, though availability varies. It is important to note that GLP-1 receptor agonists should not be combined with DPP-4 inhibitors, as per NICE guidance. Combination therapy often proves more effective than monotherapy for addressing the multiple pathophysiological defects in type 2 diabetes.

Bariatric surgery represents the most effective intervention for severe obesity-related insulin resistance, with procedures like gastric bypass producing remission of type 2 diabetes in many patients. NICE recommends considering surgery for adults with BMI ≥35 kg/m² (with lower thresholds for people from Black African, African-Caribbean, South Asian, and Chinese family backgrounds) and recent-onset type 2 diabetes. Referral to specialist weight management services should be considered for appropriate candidates who have not achieved adequate results with conventional approaches.

No, Ozempic is currently licensed in the UK only for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. It is not approved for insulin resistance alone or prediabetes, and off-label use should only be considered under specialist guidance.

Improvements in glycaemic control can be observed within weeks of starting Ozempic, but meaningful changes in insulin sensitivity typically develop over several months as weight loss progresses. Individual responses vary considerably.

Contact your GP immediately if you experience persistent vomiting or diarrhoea, severe abdominal pain, signs of allergic reaction, or changes in vision. Suspected adverse reactions should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.