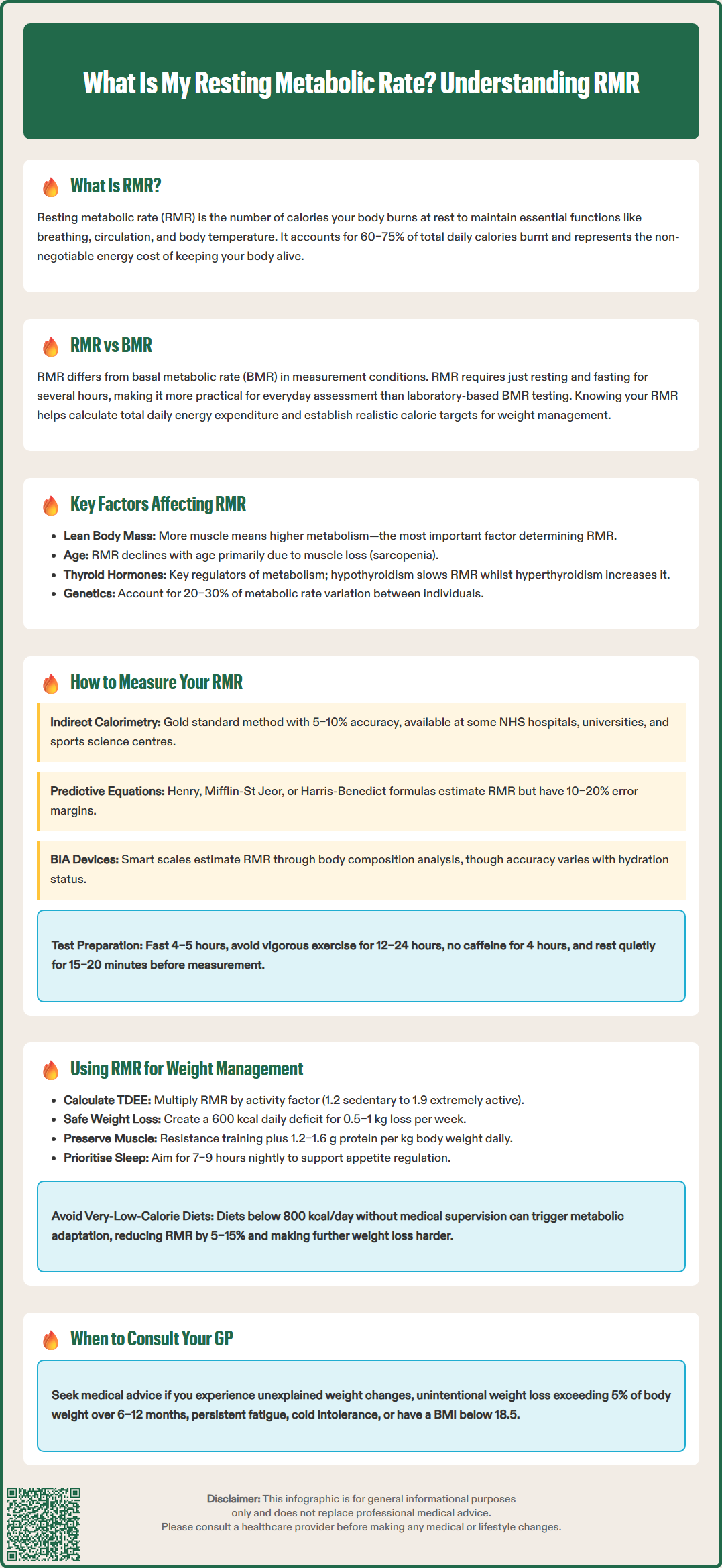

Resting metabolic rate (RMR) represents the number of calories your body requires to sustain essential physiological functions whilst at complete rest—including breathing, circulation, and maintaining body temperature. Accounting for approximately 60–75% of your total daily energy expenditure, RMR forms the foundation of your body's calorie needs. Understanding your RMR provides crucial insight for weight management, nutritional planning, and addressing metabolic conditions. Influenced by factors including body composition, age, hormones, and genetics, your RMR reflects the non-negotiable energy cost of keeping your body functioning. This article explores how RMR is measured, what affects it, and how to apply this knowledge to achieve your health goals safely and effectively.

Quick Answer: Resting metabolic rate (RMR) is the number of calories your body requires to maintain essential physiological functions whilst at complete rest, accounting for 60–75% of total daily energy expenditure.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereResting metabolic rate (RMR) refers to the number of calories your body requires to maintain essential physiological functions whilst at complete rest. These vital processes include breathing, circulation, cellular metabolism, and maintaining body temperature. RMR accounts for approximately 60–75% of total daily energy expenditure in most individuals, making it the largest component of your overall calorie needs.

Whilst often used interchangeably with basal metabolic rate (BMR), there are subtle distinctions between the two measurements. BMR is measured under strictly controlled laboratory conditions—typically after an overnight fast, in a darkened room, immediately upon waking, and in a thermoneutral environment. RMR measurements are slightly less stringent, requiring only that you are rested and have fasted for several hours, making it more practical for clinical and everyday assessment.

Understanding your RMR provides valuable insight into your body's baseline energy requirements. This knowledge forms the foundation for calculating total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), which also accounts for physical activity (both planned exercise and non-exercise activity thermogenesis) and the thermic effect of food (the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients). For individuals managing their weight, planning nutritional interventions, or addressing metabolic conditions, knowing your RMR helps establish realistic calorie targets.

Your RMR is influenced by numerous factors including body composition, age, sex, genetics, and hormonal status. Unlike voluntary energy expenditure from exercise, RMR represents the non-negotiable energy cost of simply being alive, highlighting why metabolic rate plays such a crucial role in long-term weight management and overall health.

Body composition is the most significant determinant of RMR. Lean body mass—particularly skeletal muscle—is metabolically active tissue that requires substantial energy even at rest. Individuals with greater muscle mass typically have higher RMRs than those with higher body fat percentages, as adipose tissue has lower metabolic activity than lean tissue. This explains why men generally have higher RMRs than women of similar weight, as they typically possess greater muscle mass.

Age-related changes can impact metabolic rate. RMR may decline with age, primarily due to progressive loss of lean muscle mass (sarcopenia) and hormonal changes. This relationship is complex, with recent research suggesting that when adjusted for body composition, significant changes may not occur until later adulthood. Nevertheless, maintaining muscle mass becomes increasingly important with age to support metabolic health.

Hormonal factors play a crucial regulatory role in metabolic rate. Thyroid hormones (thyroxine and triiodothyronine) are particularly important, with clinical hypothyroidism potentially decreasing RMR and hyperthyroidism potentially increasing it. The magnitude varies with severity of the condition. Other hormones including cortisol, growth hormone, and sex hormones also influence metabolic rate. Women may experience cyclical variations in RMR throughout the menstrual cycle, with slight increases during the luteal phase. Pregnancy and lactation substantially increase energy requirements.

Genetic factors contribute to inter-individual variation in RMR, with studies suggesting genetics may explain approximately 20–30% of the variance between individuals. Additional factors affecting RMR include:

Environmental temperature – cold exposure increases RMR through thermogenesis

Nutritional status – severe calorie restriction can reduce RMR as an adaptive response

Medications – some medications may affect weight or energy expenditure; never stop prescribed medicines without consulting your doctor

Medical conditions – fever, infection, and inflammatory states increase RMR

Caffeine – may temporarily increase metabolic rate, though effects are modest and short-lived

Indirect calorimetry represents the gold standard for measuring RMR in clinical and research settings. This technique analyses oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production through a metabolic cart or portable device whilst you rest quietly. The test typically requires you to lie down for 20–30 minutes in a comfortable, temperature-controlled environment, breathing normally through a mask or canopy system. The equipment calculates your RMR based on gas exchange, providing accuracy within 5–10% when performed correctly. This method is available at some NHS hospitals (typically in specialist nutrition or critical care settings), university research facilities, and private sports science centres.

For accurate indirect calorimetry results, specific preparation guidelines must be followed:

Fast for at least 4–5 hours (ideally overnight)

Avoid vigorous exercise for 12–24 hours beforehand

Refrain from caffeine and stimulants for at least 4 hours

Rest quietly for 15–20 minutes before measurement begins

Avoid smoking or alcohol consumption on the test day

Predictive equations offer a practical alternative when direct measurement is unavailable. Commonly used formulas include the Henry equations (widely used in UK clinical practice), the Mifflin-St Jeor equation, the Harris-Benedict equation, and the Cunningham equation (which accounts for lean body mass). These calculations use variables including weight, height, age, and sex to estimate RMR. Whilst convenient and cost-free, predictive equations typically have an error margin of 10–20% compared to measured values, as they cannot account for individual metabolic variations.

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) devices and smart scales increasingly offer RMR estimates alongside body composition measurements. These devices pass a small electrical current through the body to estimate lean mass, then apply predictive equations. Whilst convenient for home monitoring, accuracy varies considerably between devices and depends heavily on hydration status and measurement conditions. For clinical decision-making or precise nutritional planning, professionally measured RMR remains preferable to estimated values.

For measuring total energy expenditure in free-living conditions, doubly labelled water is considered the gold standard, though this technique measures overall energy expenditure rather than RMR specifically.

Understanding your RMR provides the foundation for evidence-based weight management. To estimate your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), multiply your RMR by an activity factor: approximately 1.2 for sedentary lifestyle, 1.375 for light activity, 1.55 for moderate activity, 1.725 for very active, or 1.9 for extremely active individuals. These multipliers are estimates and individual requirements vary. This TDEE represents your maintenance calories—the amount needed to maintain current weight. For weight loss, NICE guidance suggests a deficit of about 600 kcal daily to achieve gradual, sustainable weight reduction of approximately 0.5–1 kg per week.

It is crucial to avoid excessively low calorie intakes. Very-low-calorie diets (typically defined as <800 kcal/day) should only be undertaken with medical supervision. Consuming significantly fewer calories than needed for extended periods can trigger metabolic adaptation, where your body reduces energy expenditure as a survival mechanism. This can decrease RMR by approximately 5–15% beyond what would be expected from weight loss alone, making further weight loss increasingly difficult and potentially compromising nutritional adequacy.

Preserving or supporting RMR during weight management improves long-term success. Strategies include:

Resistance training – builds lean muscle mass, which contributes approximately 10–15 kcal per kg of muscle daily at rest

Adequate protein intake – 1.2–1.6 g per kg body weight helps preserve muscle during calorie restriction (seek dietetic advice if you have kidney disease or other health conditions)

Choosing a regular eating pattern – find an approach that supports your adherence and nutritional needs

Sufficient sleep – aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep; poor sleep affects appetite regulation and food choices

For individuals with unexplained weight changes despite appropriate calorie intake, or those experiencing symptoms such as persistent fatigue, cold intolerance, or changes in heart rate, consultation with a GP is advisable. These may indicate thyroid dysfunction or other metabolic disorders requiring investigation. Your GP can arrange appropriate blood tests, including thyroid function tests, and refer you to specialist services if needed.

Seek medical advice promptly if you experience unintentional weight loss (>5% of body weight over 6–12 months), have a BMI <18.5, or have concerns about disordered eating. Special populations including adolescents, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and those with existing health conditions should seek personalised advice from healthcare professionals. Registered dietitians can provide tailored nutritional guidance based on your measured or estimated RMR, ensuring your dietary approach is both safe and effective for your individual circumstances.

Whilst often used interchangeably, BMR is measured under strictly controlled laboratory conditions (overnight fast, darkened room, immediately upon waking), whereas RMR measurements are less stringent, requiring only that you are rested and have fasted for several hours, making it more practical for clinical assessment.

Predictive equations used in online calculators typically have an error margin of 10–20% compared to measured values, as they cannot account for individual metabolic variations. For clinical decision-making or precise nutritional planning, professionally measured RMR using indirect calorimetry remains preferable.

Resistance training to build lean muscle mass is the most effective strategy, as muscle tissue contributes approximately 10–15 kcal per kg daily at rest. Maintaining adequate protein intake (1.2–1.6 g per kg body weight) and sufficient sleep (7–9 hours) also support metabolic health.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.