Does eating more increase metabolism? This common question reflects widespread confusion about how food intake affects metabolic rate. Whilst your body does expend energy digesting food—a process called the thermic effect of food—simply eating more does not beneficially boost metabolism. Your basal metabolic rate remains relatively stable regardless of meal frequency or volume. Chronic undereating can slow metabolism through adaptive thermogenesis, but overeating leads to weight gain rather than increased metabolic rate. Understanding the evidence-based relationship between eating patterns and metabolism helps you make informed decisions about nutrition and metabolic health.

Quick Answer: Eating more food does not beneficially increase metabolism; instead, excess calories are stored as fat whilst your basal metabolic rate remains relatively stable.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

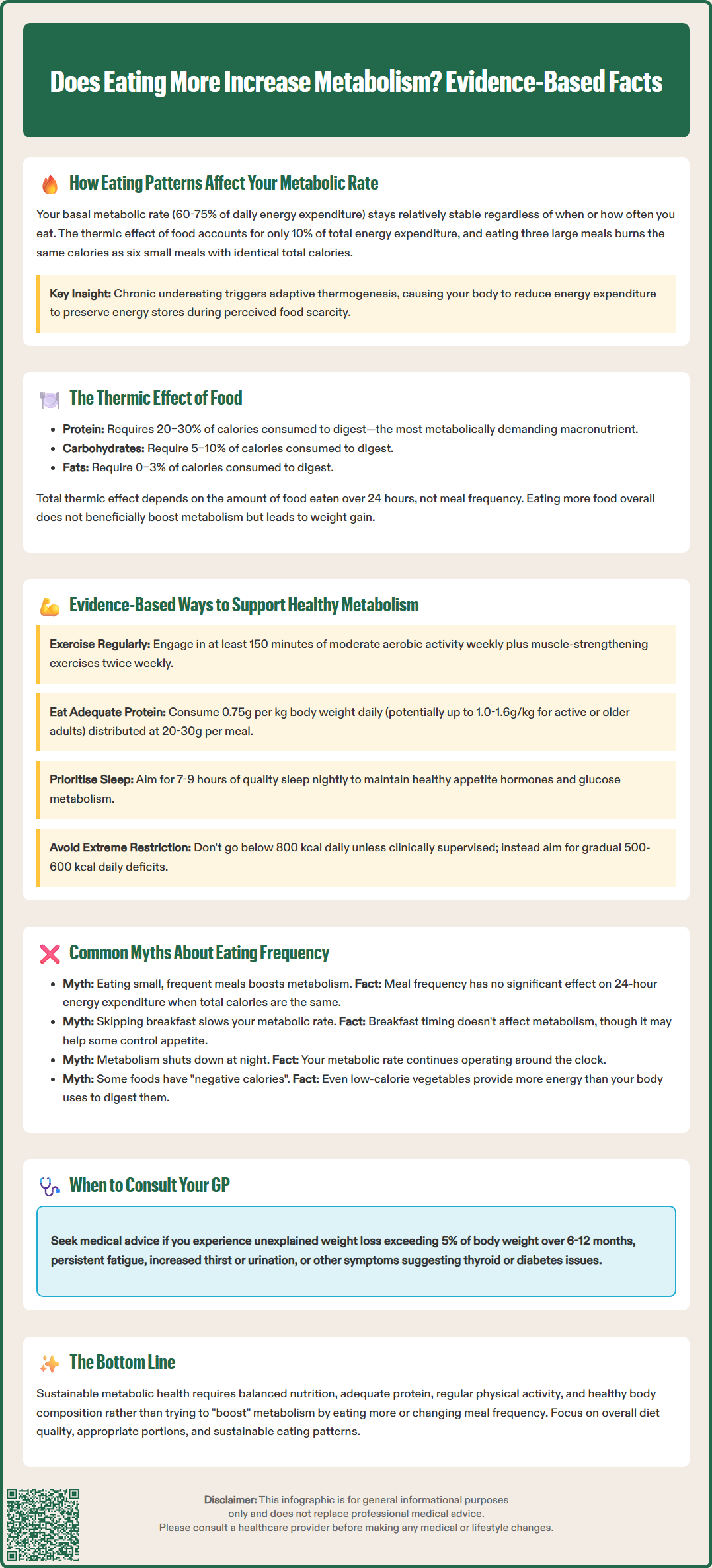

Start HereYour metabolic rate—the speed at which your body converts food into energy—is influenced by numerous factors, including age, sex, body composition, physical activity, and genetics. The relationship between eating patterns and metabolism is more nuanced than simply 'eating more increases metabolism'. In reality, your basal metabolic rate (BMR), which accounts for 60–75% of total daily energy expenditure, remains relatively stable regardless of meal frequency or timing.

When you consume food, your body does expend energy to digest, absorb, and process nutrients—a phenomenon known as the thermic effect of food (TEF) or diet-induced thermogenesis. However, this represents only approximately 10% of your total energy expenditure. The total amount of food consumed over 24 hours matters more than how frequently you eat it. Research shows that eating three larger meals versus six smaller meals with identical total calorie content produces similar metabolic effects, with no significant difference in 24-hour energy expenditure.

Chronic undereating can slow metabolism through adaptive thermogenesis, where the body reduces energy expenditure to preserve energy stores. This protective mechanism evolved to help humans survive periods of food scarcity. Most of the reduction in resting metabolic rate during dieting is explained by the loss of body mass itself, with a smaller 'adaptive' component beyond this. Conversely, consistently overeating does not proportionally increase metabolic rate; instead, excess calories are stored as adipose tissue. The body's metabolic response to food intake is governed by complex hormonal and neural pathways involving insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and thyroid hormones.

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)—the energy expended during everyday activities like fidgeting, standing, and walking—is another significant and modifiable component of daily energy expenditure.

Understanding these mechanisms helps dispel the notion that simply eating more food will 'boost' your metabolism in a beneficial way. Sustainable metabolic health depends on balanced nutrition, adequate protein intake, regular physical activity, and maintaining healthy body composition rather than manipulating meal frequency or volume.

The thermic effect of food (TEF) refers to the increase in energy expenditure that occurs after eating, as your body works to digest, absorb, transport, and store nutrients. This process typically accounts for 8–15% of total daily energy expenditure, though the exact percentage varies depending on the macronutrient composition of your diet.

Different macronutrients require varying amounts of energy to process:

Protein has the highest thermic effect (20–30% of kilocalories consumed), meaning that if you eat 100 kilocalories (kcal) of protein, approximately 20–30 kcal are used in its digestion and metabolism

Carbohydrates have a moderate thermic effect (5–10% of kilocalories consumed)

Fats have the lowest thermic effect (0–3% of kilocalories consumed)

Alcohol, whilst not a macronutrient, has a thermic effect of approximately 10–30%

It's important to note that alcohol should never be consumed for its thermic effect. The UK Chief Medical Officers advise limiting alcohol intake to no more than 14 units per week, spread over three or more days, for health reasons unrelated to metabolism.

This explains why higher-protein diets are often associated with slightly increased energy expenditure and improved satiety. However, the overall impact on weight management remains modest. Research suggests that higher protein intake typically translates to only modest additional energy expenditure for most individuals.

The total thermic effect depends on the total amount of food consumed over 24 hours rather than meal frequency. Whether you consume 2,000 kilocalories in three meals or six smaller meals, the cumulative thermic effect remains essentially the same. Your body's metabolic machinery processes the total nutrient load regardless of timing.

It's important to note that TEF represents a relatively small component of total energy expenditure compared to basal metabolic rate and physical activity. Whilst optimising protein intake can modestly support metabolic health, there is no evidence that simply eating more food overall will beneficially increase your metabolism. Instead, excess calorie consumption leads to weight gain and potential metabolic complications.

Supporting optimal metabolic function requires a comprehensive approach based on lifestyle factors rather than simply manipulating food intake. NICE guidance emphasises sustainable lifestyle modifications for maintaining healthy weight and metabolic health.

Physical activity and muscle mass are among the most effective ways to support metabolism. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, burning more kilocalories at rest than adipose tissue. The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, plus muscle-strengthening activities on at least two days per week. This helps maintain or increase lean muscle mass, which becomes particularly important with advancing age, as muscle mass naturally declines from the fourth decade onwards.

Adequate protein intake supports muscle protein synthesis and has the highest thermic effect of all macronutrients. The UK Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) is 0.75g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily for adults. Some evidence suggests that active individuals and older adults may benefit from higher intakes (1.0–1.6g/kg), though this should be discussed with a healthcare professional or registered dietitian. Distributing protein intake across meals (approximately 20–30g per meal) may help optimise muscle protein synthesis.

Sleep quality and duration significantly influence metabolic health. Sleep deprivation disrupts hormones regulating appetite (ghrelin and leptin) and glucose metabolism, potentially leading to insulin resistance. Adults should aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep nightly.

Hydration plays a role in metabolic processes, with some studies suggesting that drinking water may temporarily increase energy expenditure, though this effect is small and inconsistent. Adequate hydration (approximately 6–8 glasses daily as recommended by the NHS) supports overall physiological function.

Avoiding extreme calorie restriction is generally advisable for most people. Very low-calorie diets (below 800 kcal daily) can trigger adaptive thermogenesis, where the body reduces metabolic rate to conserve energy. However, such diets may be appropriate in specific circumstances under clinical supervision, such as in the NHS Low Calorie Diet Programme. For most people, gradual, sustainable calorie deficits of 500–600 kcal daily are more effective for weight loss whilst preserving metabolic rate, as recommended by NICE guidance.

Consult your GP if you experience unexplained weight changes (particularly unintentional weight loss >5% of body weight over 6–12 months), persistent fatigue, increased thirst or urination, tremors, palpitations, heat intolerance, or other concerning symptoms that might indicate underlying conditions such as thyroid disorders or diabetes that affect metabolism.

Several persistent myths surround eating patterns and metabolism, often perpetuated by popular media and unqualified sources. Understanding the evidence helps you make informed decisions about your dietary habits.

Myth: Eating small, frequent meals 'stokes the metabolic fire'

This widely circulated claim suggests that eating every 2–3 hours keeps metabolism elevated. However, robust evidence from systematic reviews demonstrates that meal frequency does not significantly affect 24-hour energy expenditure when total calorie intake remains constant. Whether you eat three meals or six smaller meals, the cumulative thermic effect of food remains essentially identical. There is no metabolic advantage to grazing throughout the day.

Myth: Skipping breakfast slows metabolism

Whilst breakfast consumption is associated with various health benefits in observational studies, there is no evidence that skipping breakfast inherently damages metabolic rate. Research, including controlled trials such as the Bath Breakfast Project, shows that breakfast skipping does not reduce 24-hour energy expenditure. However, breakfast may help regulate appetite and prevent overconsumption later in the day for some individuals.

Myth: Eating late at night slows metabolism

Your metabolism does not 'shut down' at night. Whilst circadian rhythms influence metabolic processes, and some evidence suggests that late-night eating may affect glucose metabolism and weight management, this relates more to total calorie intake, food choices, and alignment with circadian biology rather than metabolism 'slowing down'. The timing of meals may influence how efficiently nutrients are processed, but the fundamental metabolic rate continues throughout the 24-hour cycle.

Myth: Certain foods have 'negative calories'

No food requires more energy to digest than it provides. Whilst celery and other low-calorie vegetables have minimal caloric content and high fibre, they still provide net kilocalories after accounting for the thermic effect of food.

Evidence-based approach: Focus on total dietary quality, appropriate portion sizes, adequate protein intake, regular physical activity, and sustainable eating patterns that you can maintain long-term. If you have concerns about your metabolism or unexplained weight changes despite healthy lifestyle habits, consult your GP, who may investigate thyroid function, metabolic disorders, or other underlying conditions affecting energy balance.

No, robust evidence shows that meal frequency does not significantly affect 24-hour energy expenditure when total calorie intake remains constant. Whether you eat three meals or six smaller meals, the cumulative thermic effect of food remains essentially identical.

The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the increase in energy expenditure after eating, accounting for 8–15% of total daily energy expenditure. Protein has the highest thermic effect at 20–30%, followed by carbohydrates at 5–10%, and fats at 0–3%.

Consult your GP if you experience unexplained weight loss exceeding 5% of body weight over 6–12 months, persistent fatigue, increased thirst or urination, tremors, palpitations, or heat intolerance, as these may indicate thyroid disorders or other metabolic conditions requiring investigation.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.