Does GLP-1 help with binge eating? This question is increasingly asked as GLP-1 receptor agonists gain prominence for weight management. Whilst medications such as semaglutide and liraglutide are licensed in the UK for type 2 diabetes and obesity, their potential role in binge eating disorder remains under investigation. These agents work by mimicking a natural gut hormone that regulates appetite and satiety, prompting interest in whether they might reduce the frequency and severity of binge eating episodes. However, GLP-1 medications are not currently licensed for binge eating disorder, and psychological interventions remain the recommended first-line treatment according to NICE guidance.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists show preliminary promise in reducing binge eating episodes, but are not currently licensed for binge eating disorder in the UK and require further research.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

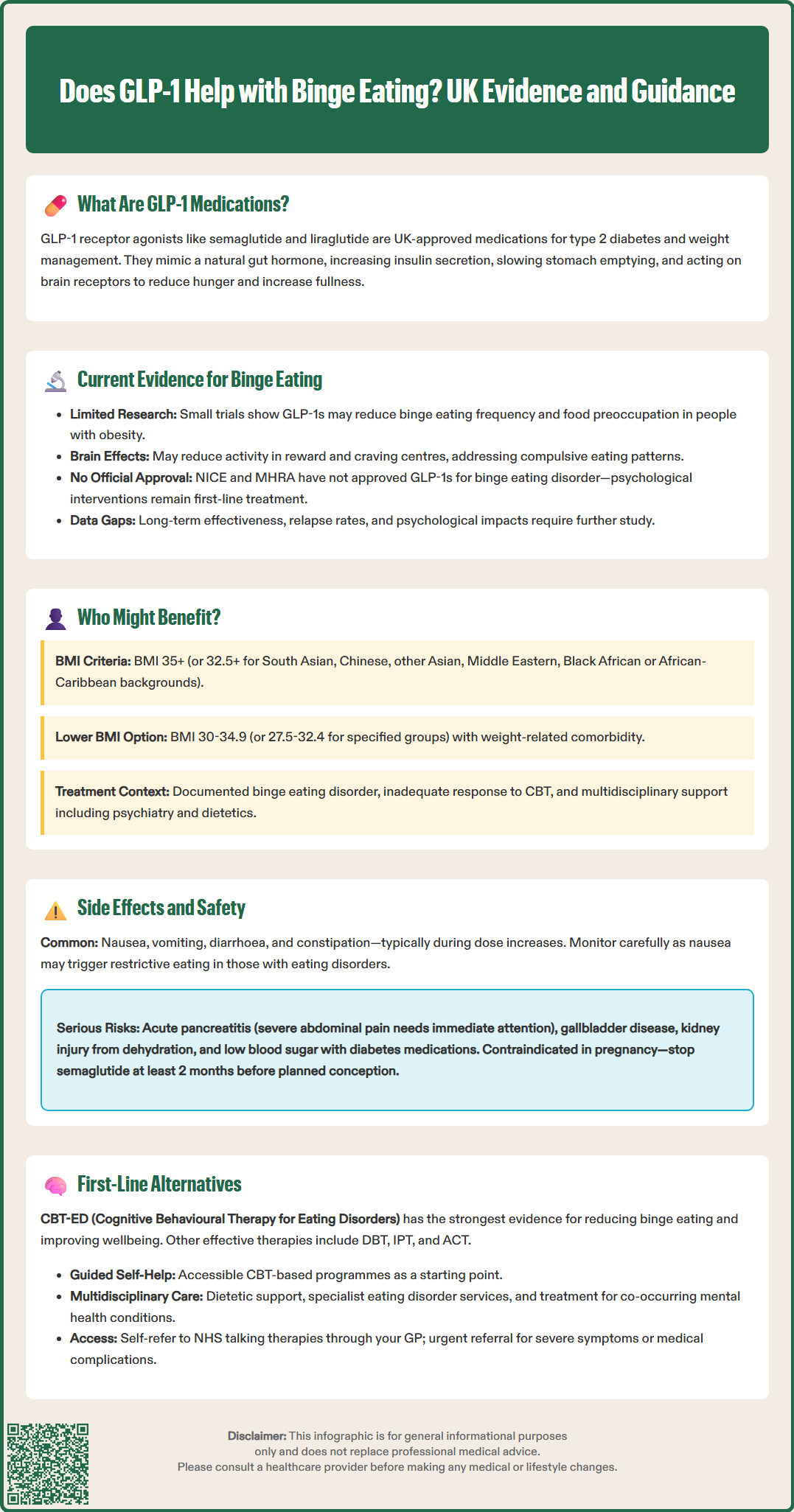

Start HereGlucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications originally developed for managing type 2 diabetes and, more recently, approved for weight management. In the UK, medications such as semaglutide (Wegovy for weight management; Ozempic for type 2 diabetes) and liraglutide (Saxenda for weight management; Victoza for type 2 diabetes) are licensed by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for these specific indications.

These medications work by mimicking the action of GLP-1, a naturally occurring hormone released by the intestine after eating. GLP-1 receptor agonists enhance insulin secretion in response to elevated blood glucose, suppress glucagon release, and slow gastric emptying. Crucially, they also act on receptors in the brain—particularly in areas regulating appetite and satiety—to reduce hunger and increase feelings of fullness.

The mechanism relevant to eating behaviour involves both peripheral and central pathways. By delaying gastric emptying, GLP-1 agonists prolong the sensation of fullness after meals. Simultaneously, their action on hypothalamic and brainstem appetite centres reduces food-seeking behaviour and overall caloric intake. This dual mechanism has prompted interest in whether these medications might help individuals struggling with binge eating disorder (BED) or recurrent binge eating episodes.

Whilst GLP-1 medications are not currently licensed specifically for binge eating disorder in the UK, emerging research is exploring their potential therapeutic role. According to NICE guidance (TA875 and TA664), GLP-1 medications for weight management should be used within specialist weight management services and are typically time-limited. Understanding how these agents influence appetite regulation provides a foundation for considering their application beyond their licensed indications.

The evidence base for GLP-1 receptor agonists in treating binge eating disorder remains preliminary but promising. Several small clinical trials and observational studies have investigated whether these medications reduce the frequency and severity of binge eating episodes.

Preliminary research, including a small randomised controlled trial published in Obesity (Robert et al., 2023), examined liraglutide in adults with binge eating disorder and obesity. Participants receiving liraglutide demonstrated a reduction in binge eating days per week compared to placebo, alongside modest weight loss. Similar findings have emerged from pilot studies of semaglutide, with participants reporting decreased loss-of-control eating and reduced preoccupation with food, though sample sizes have been limited.

Mechanistic studies suggest that GLP-1 agonists may attenuate the reward-driven aspects of eating. Neuroimaging research in obesity populations indicates these medications reduce activation in brain regions associated with food reward and craving (Ten Kulve et al., 2016), potentially addressing the compulsive nature of binge eating. However, it remains unclear whether improvements result primarily from appetite suppression, altered reward processing, or both.

Importantly, there is no official indication from NICE or the MHRA for using GLP-1 medications specifically for binge eating disorder. NICE guidance (NG69) recommends psychological interventions as first-line treatment for eating disorders. Most published studies on GLP-1 medications have focused on individuals with concurrent obesity, and evidence in normal-weight individuals with BED is limited. Longer-term data on sustained efficacy, relapse rates after discontinuation, and psychological outcomes are still needed.

Clinicians considering off-label use must weigh emerging evidence against the lack of formal guidance, ensuring shared decision-making with patients and appropriate monitoring for both physical and psychological outcomes.

Patient selection for potential GLP-1 therapy in the context of binge eating requires careful clinical assessment. Currently, these medications are most appropriately considered for individuals who meet criteria for both binge eating disorder (or recurrent binge eating) and have a body mass index (BMI) within the licensed range for weight management medications.

According to NICE technology appraisal guidance (TA875), semaglutide for weight management is recommended for adults with a BMI of 35 kg/m² or greater, or 32.5 kg/m² or greater for people from South Asian, Chinese, other Asian, Middle Eastern, Black African or African-Caribbean family backgrounds. Individuals with a BMI of 30–34.9 kg/m² (or 27.5–32.4 kg/m² for the specified ethnic groups) may be considered if they have at least one weight-related comorbidity. Treatment should be initiated and supervised within a specialist weight management service and is typically time-limited.

For liraglutide, NICE guidance (TA664) recommends similar BMI thresholds but with distinct eligibility criteria and specialist service requirements.

Ideal candidates might include those who:

Have documented binge eating episodes causing significant distress

Meet BMI criteria for weight management medications

Have not responded adequately to psychological interventions (such as cognitive behavioural therapy)

Do not have contraindications to GLP-1 therapy

Understand the off-label nature of this indication

UK SmPCs for GLP-1 medications note findings of thyroid C-cell tumours in rodent studies, though the relevance to humans remains uncertain. While not a formal contraindication in UK prescribing information, clinicians should exercise vigilance in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia. Caution is also needed in those with severe gastrointestinal disease, a history of pancreatitis, or significant psychiatric comorbidity requiring specialist input.

Any consideration of GLP-1 therapy for binge eating should occur within a multidisciplinary framework, ideally involving input from psychiatry, dietetics, and specialist weight management services, with psychological support remaining central to treatment.

Gastrointestinal adverse effects are the most commonly reported side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. Symptoms typically emerge during dose titration and often diminish over several weeks, though some individuals experience persistent gastrointestinal upset requiring dose adjustment or discontinuation.

For individuals with binge eating disorder, the psychological impact of gastrointestinal side effects warrants particular attention. Nausea and food aversion might initially seem beneficial in reducing binge episodes, but could potentially trigger restrictive eating patterns or exacerbate disordered eating cognitions in vulnerable individuals. Close monitoring of eating behaviours and psychological wellbeing is essential.

Serious but rare adverse effects include:

Acute pancreatitis (patients should be advised to seek immediate medical attention for severe, persistent abdominal pain)

Gallbladder disease, including cholecystitis and cholelithiasis

Acute kidney injury, particularly in the context of dehydration from gastrointestinal side effects

Hypoglycaemia, especially when used alongside other glucose-lowering medications

Thyroid C-cell tumours (observed in rodent studies; relevance to humans remains uncertain)

The delayed gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 medications may affect the absorption of some oral medicines. Patients should inform healthcare professionals about all medications they are taking.

Patient safety advice should include:

Reporting severe or persistent abdominal pain immediately

Maintaining adequate hydration, particularly during gastrointestinal upset

Monitoring for signs of depression or suicidal ideation (regulatory authorities are monitoring this signal, though no causal link has been established)

Understanding that rapid weight loss may necessitate adjustment of other medications

Regarding pregnancy, advice is product-specific: Wegovy and Saxenda are contraindicated in pregnancy. For semaglutide, treatment should be discontinued at least 2 months before a planned pregnancy. For liraglutide, follow the specific SmPC guidance on discontinuation timing. Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception during treatment.

Patients should contact their GP if they experience concerning symptoms and report suspected side effects via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk or via the Yellow Card app).

Psychological interventions remain the first-line, evidence-based treatment for binge eating disorder according to NICE guidance (NG69). Cognitive behavioural therapy specifically adapted for eating disorders (CBT-ED) has the strongest evidence base, with studies demonstrating significant reductions in binge eating frequency and improvements in psychological wellbeing. Guided self-help programmes based on CBT principles offer an accessible initial step for many individuals.

Other psychological approaches include:

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), which addresses emotional regulation difficulties often underlying binge eating

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), focusing on relationship patterns and emotional triggers

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), helping individuals develop psychological flexibility around food-related thoughts

Pharmacological alternatives to GLP-1 agonists are limited in the UK. Lisdexamfetamine is not licensed for binge eating disorder in the UK (though it is licensed for ADHD). Any use for binge eating would be off-label and should be specialist-initiated with appropriate monitoring due to its stimulant properties and potential for misuse.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), particularly fluoxetine at higher doses, have shown modest efficacy in reducing binge frequency, though they are not specifically licensed for this indication. NICE guidance (NG69) advises against offering medication as the sole treatment for eating disorders.

Multidisciplinary support is crucial and may include:

Dietetic input to establish regular, balanced eating patterns without rigid restriction

Specialist eating disorder services for complex presentations

Support groups (such as Beat, the UK eating disorder charity)

Treatment of co-occurring conditions such as depression, anxiety, or substance use disorders

Patients should be encouraged to access NHS talking therapies through self-referral or GP referral. For those with severe symptoms, significant medical complications, or high suicide risk, urgent referral to specialist eating disorder services is appropriate. The NHS website provides information on accessing these services. A comprehensive, individualised approach addressing both biological and psychological factors offers the best outcomes for binge eating disorder.

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not currently licensed by the MHRA specifically for binge eating disorder. They are approved only for type 2 diabetes and weight management within specialist services.

NICE guidance recommends psychological interventions, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy adapted for eating disorders (CBT-ED), as the first-line evidence-based treatment for binge eating disorder.

The most common side effects are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal discomfort. These typically emerge during dose titration and often diminish over several weeks.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.