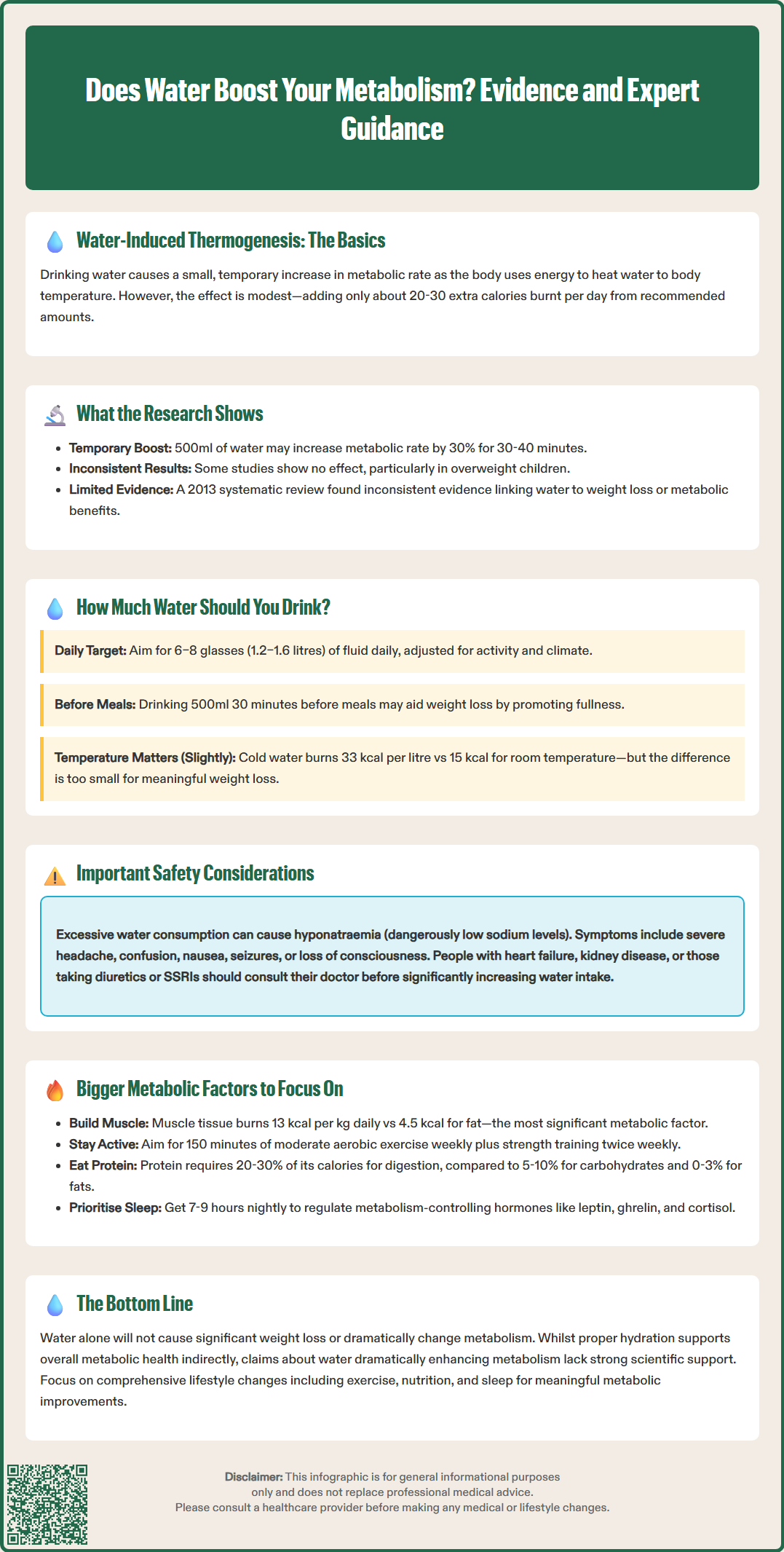

Many people wonder whether drinking water can increase the number of calories their body burns. Research suggests that water consumption may produce a modest, temporary rise in metabolic rate through a process called water-induced thermogenesis, whereby the body expends energy heating ingested water to body temperature. However, the overall impact on daily energy expenditure is relatively small—perhaps 20–30 additional kilocalories per day. Whilst adequate hydration supports numerous physiological processes essential for metabolic health, water alone is unlikely to produce significant weight loss or dramatically alter metabolic function. Understanding the evidence helps set realistic expectations about water's role in metabolism.

Quick Answer: Drinking water produces a modest, temporary increase in metabolic rate through water-induced thermogenesis, but the effect is small—approximately 20–30 additional kilocalories daily—and insufficient for significant weight loss.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereThe relationship between water consumption and metabolic rate has attracted considerable scientific interest, particularly in the context of weight management and energy expenditure. Metabolism refers to the complex biochemical processes by which the body converts food and drink into energy, measured as the number of calories burned at rest (basal metabolic rate) and during activity.

Research suggests that drinking water may produce a modest, temporary increase in metabolic rate through a process called water-induced thermogenesis. This phenomenon occurs when the body expends energy to heat ingested water to body temperature and process it through various physiological systems. However, the magnitude and clinical significance of this effect remain subjects of ongoing investigation.

Whilst some studies have demonstrated measurable increases in energy expenditure following water consumption, the overall impact on daily calorie burning is relatively small—theoretical calculations suggest perhaps 20–30 additional kilocalories (kcal) per day for someone drinking the recommended amount of water, though this varies with water temperature and volume consumed. This modest effect means that water alone is unlikely to produce significant weight loss or dramatically alter metabolic function.

It is important to maintain realistic expectations: water is not a metabolic 'miracle cure', but rather one component of overall metabolic health. Adequate hydration supports numerous physiological processes, including nutrient transport, temperature regulation, and cellular function, all of which contribute indirectly to optimal metabolic efficiency. The NHS emphasises that staying well-hydrated is essential for general health, though claims about dramatic metabolic enhancement should be viewed with appropriate scepticism.

The concept of water-induced thermogenesis was first rigorously examined in a 2003 German study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (Boschmann et al.), which reported that drinking 500ml of water increased metabolic rate by approximately 30% in healthy adults, with the effect peaking at 30–40 minutes post-consumption. The researchers attributed roughly 40% of this increase to the energy required to heat the water from room temperature (22°C) to body temperature (37°C), a process known as thermogenic response.

Subsequent research has produced mixed results, with some studies replicating these findings whilst others have found more modest or negligible effects. A 2006 study in overweight children found no significant increase in resting energy expenditure following water consumption, suggesting that the thermogenic response may vary by age, body composition, or metabolic health status. The discrepancies in research findings may also relate to methodological differences, including water temperature, volume consumed, and measurement techniques.

Some researchers have hypothesised that water consumption might activate the sympathetic nervous system, potentially leading to increased noradrenaline release and subsequent metabolic stimulation. Additionally, it has been suggested that adequate hydration may support mitochondrial function—the cellular 'powerhouses' responsible for energy production. However, these mechanisms remain largely theoretical in humans and require further investigation before firm conclusions can be drawn.

A systematic review by Muckelbauer et al. (2013) in the International Journal of Obesity examined the relationship between water consumption and weight-related outcomes, finding inconsistent evidence for metabolic effects. There is currently no UK guidance recommending water intake specifically as a metabolic intervention. The evidence, whilst suggestive of a small thermogenic effect, does not currently support water as a primary strategy for metabolic enhancement or weight management. Healthcare professionals should counsel patients that any metabolic benefit from water consumption is likely to be modest and should be considered alongside comprehensive lifestyle modifications.

The NHS Eatwell Guide recommends that adults drink 6–8 glasses (approximately 1.2–1.6 litres) of fluid daily to maintain adequate hydration, though individual requirements vary based on factors such as body size, activity level, climate, and health status. This general guidance aims to prevent dehydration rather than specifically targeting metabolic enhancement, as the primary health benefits of adequate hydration relate to maintaining physiological function.

For those interested in potential metabolic effects, research suggests that consuming water before meals may offer modest benefits. Studies have indicated that drinking approximately 500ml of water 30 minutes before eating may slightly increase energy expenditure and potentially reduce calorie intake by promoting satiety. A 2015 randomised controlled trial published in Obesity (Parretti et al.) found that adults who drank water before meals lost more weight over 12 weeks compared to those who did not, though this effect likely relates more to reduced food consumption than direct metabolic stimulation.

Water temperature may influence the thermogenic response, with cold water (approximately 3–4°C) theoretically requiring more energy to warm to body temperature than room-temperature water. Based on water's specific heat capacity, warming 1 litre of cold water (4°C) to body temperature (37°C) requires approximately 33 kcal of energy, while warming room temperature water (22°C) requires about 15 kcal. However, this additional caloric expenditure remains clinically trivial in the context of daily energy requirements and should not be the primary consideration when establishing hydration habits.

It is crucial to note that excessive water consumption can be harmful. Drinking extremely large volumes in short periods can lead to hyponatraemia (dangerously low sodium levels), a potentially serious condition. Warning signs include severe headache, confusion, nausea, vomiting, and in severe cases, seizures or loss of consciousness—all requiring immediate medical attention. Individuals with certain medical conditions, including heart failure, kidney disease, or those taking specific medications (such as diuretics or SSRIs), should consult their GP before significantly increasing water intake. The focus should remain on consistent, moderate hydration throughout the day rather than consuming large volumes specifically for metabolic purposes.

Whilst water consumption may contribute modestly to metabolic function, numerous other factors exert far more substantial influences on metabolic rate. Understanding these variables provides a more comprehensive approach to metabolic health than focusing solely on hydration.

Body composition represents one of the most significant determinants of metabolic rate. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, burning approximately 13 kcal per kilogram daily at rest, compared to just 4.5 kcal per kilogram for fat tissue. Consequently, individuals with greater muscle mass typically have higher basal metabolic rates. Resistance training and adequate protein intake (the UK Reference Nutrient Intake is 0.75g per kilogram of body weight daily, as per the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition) support muscle maintenance and development.

Age and hormonal status affect metabolism, though recent research suggests the relationship is complex. While some decline in metabolic rate occurs with ageing, this appears more closely linked to changes in body composition and physical activity than to age itself. Thyroid hormones, particularly thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are crucial regulators of metabolic rate. Individuals experiencing unexplained weight changes, persistent fatigue, or temperature sensitivity should consult their GP, as these may indicate thyroid dysfunction requiring investigation through blood tests (TSH, free T4) as outlined in NICE guideline NG145 on thyroid disease management.

Physical activity remains the most modifiable factor influencing total daily energy expenditure. Both structured exercise and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)—the energy expended during daily activities like walking, standing, and fidgeting—contribute significantly to calorie burning. The UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, combined with strength training on two or more days.

Dietary factors beyond hydration also influence metabolic rate. The thermic effect of food (TEF)—the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients—varies by macronutrient: protein has the highest TEF (20–30% of calories consumed), followed by carbohydrates (5–10%) and fats (0–3%). Adequate calorie intake is essential; severe caloric restriction can trigger metabolic adaptation, reducing metabolic rate as a protective mechanism.

Sleep quality and stress management represent often-overlooked metabolic factors. Chronic sleep deprivation disrupts hormones regulating appetite and metabolism, including leptin and ghrelin, whilst elevating cortisol levels. The NHS recommends 7–9 hours of quality sleep nightly for adults. Similarly, chronic psychological stress can alter metabolic function through sustained cortisol elevation and its effects on insulin sensitivity and fat storage.

Patients concerned about metabolic function should adopt a holistic approach incorporating adequate hydration, balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, stress management, and sufficient sleep. Those experiencing unexplained weight changes, persistent fatigue, or other concerning symptoms should seek medical evaluation to exclude underlying conditions such as hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or diabetes mellitus.

If you experience side effects to any medicines or vaccines, you can report these via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme at yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk.

The NHS recommends 6–8 glasses (1.2–1.6 litres) of fluid daily for adequate hydration. Research suggests drinking approximately 500ml of water 30 minutes before meals may produce modest metabolic effects, though the overall impact on daily calorie burning remains small.

Cold water (3–4°C) requires more energy to warm to body temperature than room-temperature water—approximately 33 kilocalories per litre versus 15 kilocalories. However, this difference is clinically trivial and should not be the primary consideration for hydration habits.

Body composition (particularly muscle mass), physical activity levels, thyroid function, sleep quality, stress management, and dietary factors exert substantially greater influence on metabolic rate than water consumption. A holistic approach incorporating these elements is most effective for metabolic health.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.