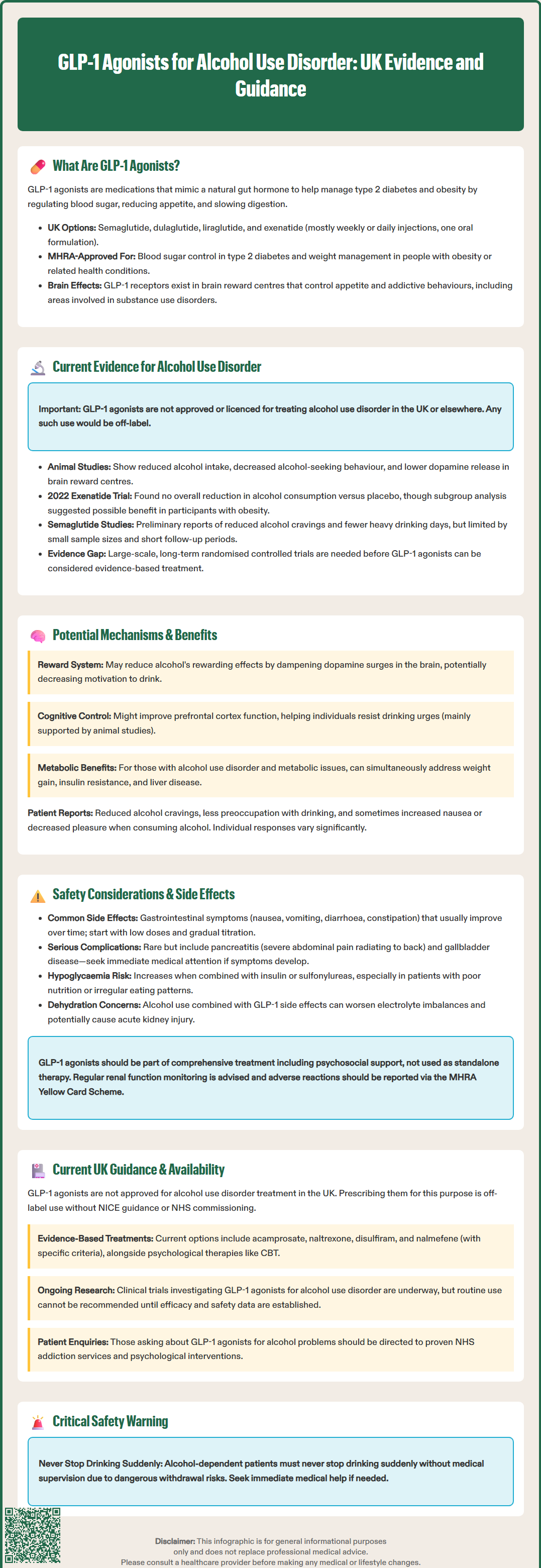

GLP-1 agonists for alcohol use disorder represent an emerging area of research interest, though these medications remain unlicensed for this indication in the UK. Originally developed for type 2 diabetes and obesity, GLP-1 agonists such as semaglutide and liraglutide are now being investigated for their potential effects on alcohol consumption. Early preclinical and small-scale human studies suggest these drugs may influence brain reward pathways involved in addictive behaviours, potentially reducing alcohol cravings and intake. However, robust clinical trial evidence is lacking, and current NICE guidance does not recommend GLP-1 agonists for treating alcohol use disorder. Established pharmacological options including acamprosate, naltrexone, and nalmefene remain the evidence-based first-line treatments.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 agonists are not currently approved or recommended for treating alcohol use disorder in the UK, though early research suggests potential effects on alcohol consumption via brain reward pathways.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereGlucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists are a class of medications originally developed to manage type 2 diabetes mellitus and, more recently, obesity. These drugs mimic the action of naturally occurring GLP-1, an incretin hormone produced in the intestine in response to food intake. GLP-1 plays a crucial role in glucose homeostasis by stimulating insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, suppressing glucagon release, and slowing gastric emptying.

GLP-1 agonists available in the UK include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and exenatide (Bydureon BCise). Most are administered via subcutaneous injection either once daily or once weekly, though oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) is taken daily by mouth. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has approved these agents for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes and, in specific formulations and doses (semaglutide as Wegovy and liraglutide as Saxenda), for weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities.

Beyond their metabolic effects, GLP-1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, particularly in brain regions involved in reward processing, appetite regulation, and addictive behaviours. This includes the nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, and prefrontal cortex—areas implicated in substance use disorders. The presence of GLP-1 receptors in these reward pathways has prompted researchers to investigate whether GLP-1 agonists might influence behaviours beyond eating, including alcohol consumption. Emerging preclinical and clinical evidence suggests these medications may modulate reward-seeking behaviour and reduce the reinforcing effects of alcohol, though this remains an area of active investigation rather than established clinical practice.

The potential role of GLP-1 agonists in treating alcohol use disorder (AUD) has emerged from both animal studies and early-phase human trials, though it is important to emphasise that there is no official licence for these medications in AUD treatment in the UK or elsewhere. Preclinical research in rodent models has consistently demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor activation reduces voluntary alcohol intake, decreases alcohol-seeking behaviour, and attenuates alcohol-induced dopamine release in reward centres of the brain.

Several small-scale human studies have begun to explore these findings in clinical populations. A randomised controlled trial published in 2022 examined exenatide in individuals with AUD, finding no significant overall difference in alcohol consumption compared to placebo over a 26-week period, though a predefined subgroup analysis showed potential benefit specifically in participants with obesity. Similarly, observational studies using healthcare databases have suggested that patients prescribed GLP-1 agonists for diabetes or obesity appear to have lower rates of alcohol-related hospital admissions and reduced self-reported drinking compared to those on other medications, though these findings are limited by potential confounding factors.

Preliminary pilot studies investigating semaglutide in people with AUD have reported early signals, with some participants experiencing reduced alcohol cravings and fewer heavy drinking days. However, these studies have been limited by small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and heterogeneous patient populations. The mechanisms observed in controlled laboratory settings may not fully translate to real-world clinical outcomes, and the durability of any effect remains uncertain.

It is crucial to note that whilst these early findings are encouraging, GLP-1 agonists are not currently recommended or approved for AUD treatment by NICE, the MHRA, or other regulatory bodies. Any use for this purpose would be off-label. Further large-scale, randomised controlled trials with longer follow-up are needed before these medications can be considered an evidence-based treatment option for alcohol use disorder.

The proposed mechanisms by which GLP-1 agonists may reduce alcohol consumption involve complex interactions within the brain's reward circuitry. GLP-1 receptors in the mesolimbic dopamine system—the primary pathway mediating reward and reinforcement—appear to modulate the pleasurable effects of alcohol. Preclinical studies suggest that by activating these receptors, GLP-1 agonists may dampen the dopamine surge typically triggered by alcohol consumption, thereby potentially reducing its rewarding properties and decreasing the motivation to drink.

Additionally, GLP-1 signalling in the prefrontal cortex may hypothetically enhance cognitive control and decision-making processes, potentially helping individuals resist urges to drink, though this mechanism is primarily supported by animal models rather than human data. The medications' effects on appetite regulation and satiety might also play an indirect role, as some individuals report that reduced overall appetite extends to diminished desire for alcohol. The slowing of gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 agonists could theoretically alter alcohol absorption patterns, though this mechanism remains speculative in the context of AUD.

Beyond neurobiological effects, GLP-1 agonists may offer additional benefits for some individuals with AUD who have co-occurring metabolic conditions. Some people with alcohol use disorder experience weight gain, insulin resistance, and metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). The metabolic improvements associated with GLP-1 agonist therapy—including weight loss, improved glycaemic control, and potential benefits in MASLD (formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease)—could address multiple health concerns simultaneously, though effects specifically in alcohol-related liver disease are not established.

Patients in early studies have reported reduced alcohol cravings, decreased preoccupation with drinking, and greater ease in abstaining from alcohol. Some describe a subjective change in how alcohol makes them feel, with diminished pleasure or increased nausea when drinking. However, individual responses vary considerably, and not all patients experience these effects. The extent to which these subjective changes translate into sustained behavioural change and improved clinical outcomes requires further investigation through rigorous clinical trials.

When considering GLP-1 agonists for any indication, clinicians and patients must be aware of the established side effect profile of these medications. The most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. These symptoms typically occur during treatment initiation or dose escalation and often improve over time, though they can be severe enough to necessitate discontinuation in some patients. Starting with a low dose and titrating gradually can help minimise these effects.

Pancreatitis is a rare but serious potential complication associated with GLP-1 agonist use. Patients should be counselled to seek immediate medical attention if they experience severe, persistent abdominal pain radiating to the back, particularly if accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Gallbladder disease (including cholelithiasis and cholecystitis) has been reported, particularly with rapid weight loss. UK SmPCs note that in rodent studies, some GLP-1 agonists caused thyroid C-cell tumours, though the clinical relevance in humans is unknown; patients should report any thyroid symptoms (e.g., neck mass, dysphagia, persistent hoarseness).

For individuals with alcohol use disorder specifically, additional safety considerations arise. Hypoglycaemia risk is generally low with GLP-1 agonists alone but may be elevated when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, particularly in patients with poor nutritional status or irregular eating patterns. Dose adjustments of these medications may be necessary. Dehydration from alcohol use combined with GLP-1-induced gastrointestinal side effects could exacerbate electrolyte imbalances and potentially lead to acute kidney injury. There is also concern about medication adherence in a population that may struggle with consistent self-care behaviours.

Semaglutide may worsen diabetic retinopathy in some patients with pre-existing disease, particularly during rapid improvement in glucose control. GLP-1 agonists are not recommended in severe renal impairment (exenatide should be avoided if eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m²), and caution is needed in moderate impairment. These medications are contraindicated during pregnancy when used for weight management, and generally not recommended during breastfeeding.

Patients should be advised to contact their GP if they experience persistent vomiting, signs of dehydration, severe abdominal pain, or symptoms of hypoglycaemia (sweating, tremor, confusion, palpitations). Regular monitoring of renal function is advisable. Suspected adverse reactions should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk). As with any treatment for substance use disorders, GLP-1 agonist therapy—if used—should be part of a comprehensive approach including psychosocial support, rather than a standalone intervention.

At present, there is no NICE guidance, MHRA approval, or NHS commissioning pathway for the use of GLP-1 agonists in treating alcohol use disorder. These medications remain licensed exclusively for type 2 diabetes mellitus and, in specific formulations and doses, for weight management in obesity. Prescribing GLP-1 agonists for AUD would constitute off-label use, which requires careful consideration of the evidence base, documented informed consent, clear rationale, appropriate monitoring, and adherence to local governance frameworks.

Current NICE guidance for alcohol use disorder (CG115) recommends a stepped-care approach beginning with brief interventions and psychological therapies, progressing to specialist assessment and treatment for moderate to severe AUD. Pharmacological options with established evidence include acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram for maintaining abstinence. Nalmefene is recommended (TA325) for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence who have a high drinking risk level (more than 60g/7.5 units daily for men, or more than 40g/5 units daily for women) without physical withdrawal symptoms and not requiring immediate detoxification, specifically when used alongside continuous psychosocial support. These remain the first-line pharmacological treatments supported by robust clinical trial evidence and cost-effectiveness analyses.

Clinicians interested in the potential of GLP-1 agonists for AUD should be aware that several clinical trials are currently underway in the UK and internationally. These studies aim to establish efficacy, optimal dosing, treatment duration, and patient selection criteria. Until such evidence emerges and undergoes regulatory review, routine use cannot be recommended.

Patients enquiring about GLP-1 agonists for alcohol problems should be directed to evidence-based treatments currently available through NHS addiction services, including community alcohol teams, specialist clinics, and psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational enhancement therapy. Those with co-occurring obesity or type 2 diabetes may be eligible for GLP-1 agonist therapy for these licensed indications, and any observed effects on alcohol consumption could be monitored and reported as part of ongoing research efforts.

Importantly, patients who are alcohol dependent should not stop drinking suddenly without medical supervision, as this can lead to potentially dangerous withdrawal symptoms. If experiencing withdrawal symptoms or needing urgent help with alcohol problems, patients should contact their GP, NHS 111, local alcohol services, or in emergencies, call 999. Healthcare professionals should remain alert to emerging evidence in this rapidly evolving field whilst maintaining focus on proven therapeutic approaches.

No, GLP-1 agonists are not approved by the MHRA or recommended by NICE for alcohol use disorder. They remain licensed only for type 2 diabetes and obesity, and any use for alcohol problems would be off-label.

NICE recommends acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram for maintaining abstinence, and nalmefene for reducing consumption in specific patient groups. All pharmacological treatments should be combined with psychosocial support.

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal discomfort, particularly during treatment initiation. Rare but serious risks include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and potential hypoglycaemia when combined with certain diabetes medications.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.