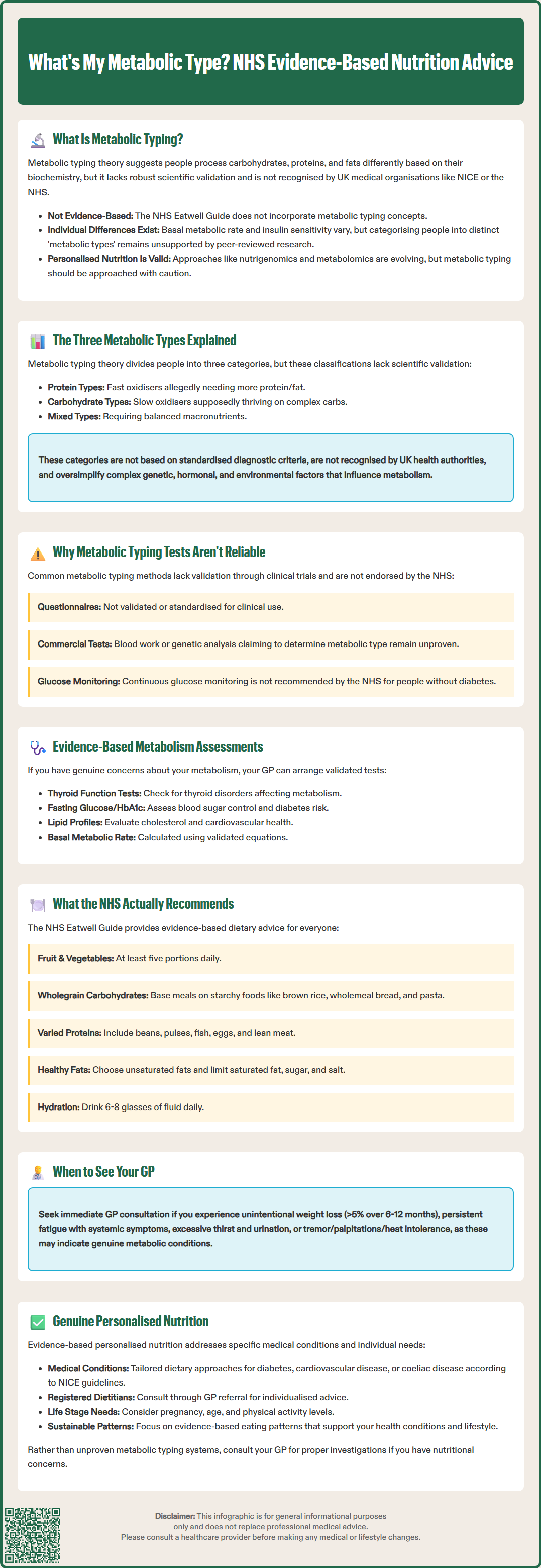

Many people wonder about their metabolic type, hoping personalised nutrition might unlock better energy, weight management, or overall health. Metabolic typing theory suggests individuals process carbohydrates, proteins, and fats differently based on unique biochemical traits. However, this concept lacks robust scientific validation and is not recognised by UK health authorities including the NHS or NICE. Whilst individual metabolic differences certainly exist—such as variations in basal metabolic rate and insulin sensitivity—categorising people into distinct 'metabolic types' remains unsupported by peer-reviewed research. Evidence-based approaches focusing on overall dietary patterns and individual health conditions remain the gold standard for personalised nutrition in the UK.

Quick Answer: Metabolic typing is an unvalidated theory suggesting people process macronutrients differently, but it lacks scientific evidence and is not recognised by the NHS or NICE.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereThe concept of metabolic typing suggests that individuals process macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—differently based on their unique biochemical makeup. Proponents of this theory argue that understanding your metabolic type can help optimise dietary choices, improve energy levels, and support weight management. The underlying premise is that people have varying rates of cellular oxidation and different autonomic nervous system dominance, which theoretically influences how efficiently they metabolise different foods.

However, it is important to note that metabolic typing lacks robust scientific validation and is not recognised by mainstream medical organisations in the UK, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) or the NHS. The NHS Eatwell Guide, which forms the foundation of official UK dietary advice, does not incorporate metabolic typing concepts. Whilst individual metabolic differences certainly exist—such as variations in basal metabolic rate, insulin sensitivity, and genetic factors affecting nutrient metabolism—the categorisation of people into distinct 'metabolic types' remains largely unsupported by peer-reviewed research.

The appeal of metabolic typing lies in its promise of personalised nutrition, which resonates with the growing interest in individualised healthcare. Many people experience frustration when generic dietary advice fails to produce desired results, leading them to seek more tailored approaches. Whilst personalisation in nutrition is a valid and evolving field, particularly in areas like nutrigenomics and metabolomics, the specific framework of metabolic typing should be approached with caution.

For those interested in optimising their diet, evidence-based approaches focusing on overall dietary patterns, portion control, and individual health conditions remain the gold standard. The British Dietetic Association (BDA) recommends consulting with registered dietitians or healthcare professionals to ensure that dietary modifications are safe, appropriate, and grounded in scientific evidence rather than unproven theories.

Metabolic typing theory typically categorises individuals into three main types: protein types, carbohydrate types, and mixed types. Each classification is said to reflect how the body preferentially processes and utilises different macronutrients for energy production.

Protein types are characterised as having a fast oxidative rate, meaning they burn through carbohydrates quickly and require more protein and fat to maintain stable blood glucose levels and sustained energy. Advocates suggest these individuals may experience fatigue, irritability, or cravings when consuming high-carbohydrate meals. The recommended dietary approach for protein types emphasises higher proportions of protein and healthy fats, with moderate carbohydrate intake focusing on low-glycaemic options.

Carbohydrate types are described as slow oxidisers who metabolise carbohydrates more efficiently and may feel sluggish or gain weight when consuming excessive protein or fat. These individuals are thought to thrive on diets higher in complex carbohydrates, with moderate protein and lower fat intake. Proponents claim carbohydrate types often have lower appetites and may prefer lighter meals.

Mixed types fall somewhere between the two extremes, theoretically requiring a balanced intake of all three macronutrients in relatively equal proportions. These individuals are said to have moderate oxidative rates and may tolerate a wider variety of dietary patterns without significant adverse effects.

It must be emphasised that there is no official link between these classifications and validated metabolic or physiological markers. The categorisation is not based on standardised diagnostic criteria recognised by UK health authorities or supported by NICE guidelines. Individual metabolic differences are far more complex than these simplified categories suggest, involving numerous genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors that cannot be reduced to three distinct types.

It's worth noting that restrictive macronutrient distributions based on these unvalidated types may be inappropriate or potentially harmful for certain groups, including people with chronic kidney disease, pregnant women, or those with a history of disordered eating. Any significant dietary changes should be discussed with healthcare professionals.

Various methods have been proposed for identifying one's metabolic type, though none have been validated through rigorous clinical trials or endorsed by UK medical authorities. The most common approach involves completing questionnaires that assess dietary preferences, energy patterns, appetite characteristics, and responses to different foods. These self-assessment tools typically ask about factors such as meal frequency preferences, post-meal energy levels, food cravings, and physical characteristics.

Some practitioners offer more elaborate testing, including:

Dietary response assessments: Monitoring how you feel after consuming meals with different macronutrient ratios

Physical and psychological symptom tracking: Recording energy levels, mood, sleep quality, and digestive comfort

Body composition analysis: Measuring changes in weight and body composition in response to dietary modifications

Blood glucose monitoring: Observing glycaemic responses to various foods

Regarding blood glucose monitoring, it's important to clarify that continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) or routine blood glucose testing is not recommended by the NHS for people without diabetes and should not be used for 'metabolic typing'.

Certain commercial services claim to determine metabolic type through blood tests, genetic analysis, or other biomarkers. However, these tests are not standardised, and their validity remains unproven. The NHS does not offer metabolic typing assessments, as the concept lacks sufficient evidence to warrant clinical application.

For individuals genuinely concerned about their metabolism, evidence-based assessments are available through healthcare providers. These include:

Thyroid function tests: To identify conditions like hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism that genuinely affect metabolic rate (NICE NG145)

Fasting glucose and HbA1c: To assess glucose metabolism and diabetes risk (HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol [6.5%] indicates diabetes; 42–47 mmol/mol [6.0–6.4%] indicates non-diabetic hyperglycaemia)

Lipid profiles: To evaluate cardiovascular risk factors

Basal metabolic rate calculations: Based on validated equations considering age, sex, weight, and height

Seek prompt GP advice if you experience concerning symptoms such as:

Unintentional weight loss (>5% body weight over 6–12 months)

Persistent fatigue with other systemic symptoms

Increased thirst and frequent urination (polyuria/polydipsia)

Tremor, palpitations, or heat intolerance

These could indicate underlying metabolic conditions requiring proper investigation. The NHS Health Check programme also offers cardiovascular and diabetes risk assessment for eligible adults. For personalised nutritional guidance, ask your GP about referral to a registered dietitian.

The NHS advocates for evidence-based approaches to personalised nutrition that consider individual health conditions, lifestyle factors, and nutritional requirements rather than unproven metabolic typing systems. The NHS Eatwell Guide remains the foundation of dietary advice in the UK, recommending a balanced diet comprising:

At least five portions of varied fruit and vegetables daily

Base meals on higher-fibre starchy carbohydrates (wholegrain options preferred)

Include beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat, and other proteins

Choose unsaturated oils and spreads in small amounts

Consume dairy or dairy alternatives (lower-fat and lower-sugar options)

Limit foods high in fat, salt, and sugar

Stay well hydrated with 6–8 glasses of fluid daily

Genuine personalisation of nutrition should account for specific medical conditions. For instance, individuals with type 1 diabetes benefit from carbohydrate counting and structured education programmes (NICE NG17), while those with type 2 diabetes require individualised dietary approaches focusing on sustainable eating patterns and sometimes energy deficit (NICE NG28). Those with cardiovascular disease require attention to saturated fat, salt, and fibre intake according to NICE guidance NG238. People with coeliac disease must strictly avoid gluten (NICE NG20), whilst those with food allergies or intolerances need appropriate exclusions and nutritional adequacy monitoring.

Emerging areas of personalised nutrition with scientific credibility include nutrigenomics—studying how genetic variations affect nutrient metabolism—and metabolomics—analysing metabolic profiles to guide dietary interventions. However, these fields remain largely in research phases, with limited clinical application currently available through the NHS.

For practical, individualised dietary advice, the NHS recommends:

Consulting registered dietitians: Available through GP referral for medical nutrition therapy

Using validated tools: Such as the NHS BMI calculator and portion size guides

Considering life stage needs: Pregnancy, lactation, childhood, and older age have specific requirements

Addressing activity levels: Physical activity significantly influences energy and nutrient needs

Rather than seeking to identify a metabolic type, focus on sustainable dietary patterns that align with evidence-based guidelines, support your health conditions, and fit your lifestyle. If you have concerns about your weight, energy levels, or nutritional status, your GP can arrange appropriate investigations and referrals to ensure any dietary modifications are safe, effective, and tailored to your genuine physiological needs rather than theoretical classifications.

No, metabolic typing is not recognised by the NHS, NICE, or other UK health authorities as it lacks robust scientific validation and peer-reviewed evidence to support its classifications.

Follow the NHS Eatwell Guide and consult your GP for referral to a registered dietitian who can provide evidence-based personalised nutrition advice tailored to your specific health conditions, life stage, and activity levels.

Evidence-based metabolic assessments available through your GP include thyroid function tests, HbA1c for glucose metabolism, lipid profiles for cardiovascular risk, and basal metabolic rate calculations based on validated equations.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.