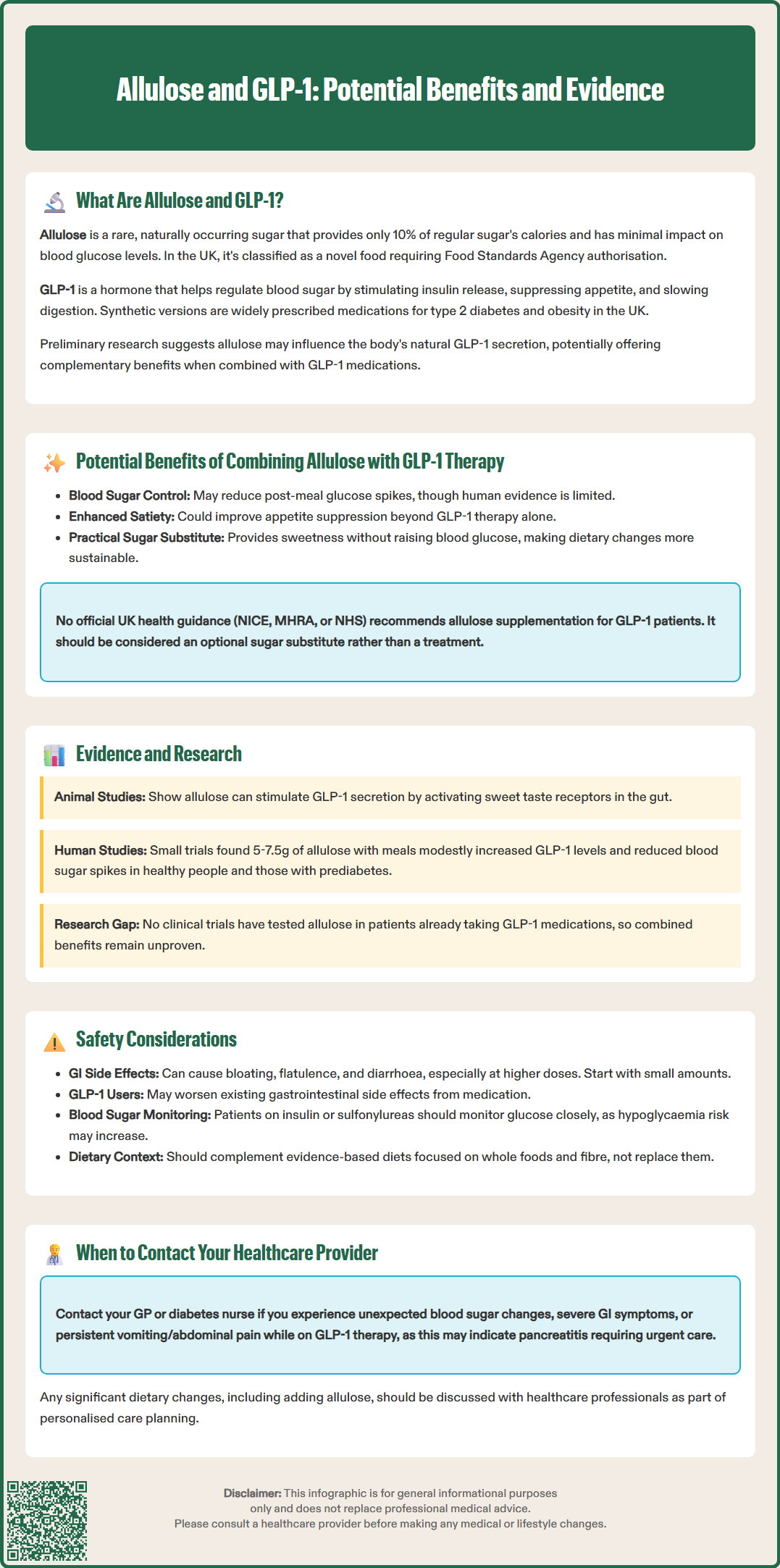

Allulose, a rare low-calorie sugar, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent two distinct approaches to managing blood glucose and weight. GLP-1 therapies such as semaglutide and liraglutide are established treatments for type 2 diabetes and obesity, recommended in NICE guidance. Emerging research suggests allulose may modestly influence endogenous GLP-1 secretion, raising questions about potential complementary benefits when used alongside prescribed GLP-1 medications. Whilst mechanistic rationale exists, clinical evidence remains limited and no UK guidance currently recommends allulose supplementation for patients receiving GLP-1 therapy. This article examines the theoretical interactions, available evidence, and safety considerations for individuals exploring dietary strategies alongside GLP-1 treatment.

Quick Answer: Allulose may modestly increase endogenous GLP-1 secretion and could theoretically complement GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy, though robust clinical evidence for combined benefits is currently lacking.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereAllulose is a rare sugar (also known as D-psicose) that occurs naturally in small quantities in foods such as wheat, figs, and raisins. Structurally similar to fructose, allulose provides approximately 0.4 kilocalories per gram—about 10% of the energy content of regular sugar—and is minimally metabolised by the human body. It has gained attention as a low-calorie sweetener that has minimal effects on blood glucose levels in most studies, making it of potential interest in diabetes management and weight control strategies.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone produced by enteroendocrine L-cells in the distal small intestine and colon in response to nutrient intake. GLP-1 plays a crucial role in glucose homeostasis by stimulating insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, suppressing glucagon release, slowing gastric emptying, and promoting satiety through central nervous system pathways. GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and dulaglutide) are now widely prescribed medications for type 2 diabetes and obesity management, approved by the MHRA and recommended in NICE guidelines (NG28 for type 2 diabetes; TA875 for semaglutide in obesity).

The potential interaction between allulose consumption and GLP-1 activity has emerged as an area of scientific interest. Preliminary research suggests that allulose may influence the secretion or activity of endogenous GLP-1, potentially offering complementary benefits when used alongside GLP-1-based therapies. Understanding how these two agents might work together could inform dietary strategies for patients receiving GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment, though it is important to note that research in this area remains in relatively early stages.

In the UK, D-allulose is classified as a novel food and requires authorisation from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) before widespread commercial use, with specific conditions of use that must be followed.

The theoretical benefits of combining allulose with GLP-1 therapy centre on enhanced glycaemic control and weight management. Proposed mechanisms include reduced postprandial glucose excursions, potentially through delayed glucose absorption and modest increases in endogenous GLP-1 secretion, though human evidence remains limited and of low certainty. When used alongside GLP-1 receptor agonists, this could theoretically provide additive glucose-lowering effects without increasing hypoglycaemia risk for most patients, as both agents work through glucose-dependent mechanisms. However, patients also taking insulin or sulfonylureas should monitor blood glucose carefully, as reduced carbohydrate intake may necessitate medication adjustments to prevent hypoglycaemia.

Appetite regulation and satiety represent another potential area of synergy. GLP-1 receptor agonists are well-established for their appetite-suppressing effects, which contribute significantly to their weight loss benefits. Some preliminary evidence suggests that allulose may also influence satiety signals and reduce overall energy intake, possibly through effects on gut hormone secretion including GLP-1. The combination might therefore enhance feelings of fullness and support adherence to reduced-calorie dietary patterns, which are fundamental to successful weight management, though individual responses may vary considerably.

Reduced reliance on conventional sugars is a practical benefit for patients using GLP-1 therapies who are working to modify their diet. Allulose provides sweetness without the glycaemic impact of sucrose or glucose, potentially making dietary changes more sustainable. For individuals prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists as part of a comprehensive diabetes or obesity management plan, incorporating allulose as a sugar substitute could support treatment goals without compromising palatability.

It is important to emphasise that there is no NICE, MHRA or NHS guidance specifically recommending allulose supplementation for patients on GLP-1 therapy. The evidence base remains limited, and dietary modifications should focus on established patterns recommended by NICE and Diabetes UK, with allulose as an optional sugar substitute rather than a treatment. Any significant dietary changes should be discussed with healthcare professionals as part of individualised care planning.

Current research on the interaction between allulose and GLP-1 is predominantly preclinical and small acute randomised crossover studies, with limited large-scale human trials specifically examining their combined effects. Animal studies have demonstrated that allulose administration can stimulate GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L-cells, potentially through activation of sweet taste receptors (T1R2/T1R3) expressed in the gut epithelium. These receptors, when activated by allulose, may trigger signalling cascades that promote incretin hormone release, though the magnitude and clinical significance of this effect in humans requires further investigation.

Small human studies have shown that allulose consumption can modestly increase postprandial GLP-1 levels compared to control conditions. Research published in journals such as Nutrition found that single doses of allulose (5–7.5 g) consumed with a meal resulted in measurable increases in plasma GLP-1 concentrations alongside reduced glucose excursions. However, these studies typically involved healthy volunteers or individuals with prediabetes rather than patients already receiving GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy, limiting direct applicability to the clinical question of combination benefits.

No randomised controlled trials have yet been published specifically evaluating allulose supplementation in patients prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetes or obesity. The absence of such evidence means that any potential additive or synergistic effects remain theoretical and clinical benefit is unproven. Furthermore, the doses of allulose used in research studies (typically 5–10 g per serving) may differ from amounts consumed through commercial food products containing allulose as a sweetener.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has assessed D-allulose for safety as a novel food, establishing specific uses and levels considered safe for consumption. In the UK, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) regulates allulose as a novel food requiring authorisation before widespread commercial use. Healthcare professionals should be aware that whilst the mechanistic rationale for allulose-GLP-1 interaction exists, robust clinical evidence supporting therapeutic recommendations is currently lacking.

D-allulose has been assessed by EFSA as safe at specified uses and levels, though UK authorisation conditions apply. The primary adverse effect is gastrointestinal discomfort, including bloating, flatulence, and diarrhoea, particularly at higher doses. These effects are similar to those seen with other low-calorie sweeteners and typically resolve with reduced intake. It is advisable to start with small amounts and gradually increase to assess individual tolerance. Patients with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, may be more susceptible to these symptoms.

For individuals currently prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists, there are no specific contraindications to consuming allulose-containing foods within FSA-authorised conditions, but caution is warranted due to potential additive gastrointestinal effects. Patients should be counselled that allulose is not a substitute for prescribed medication and should not be viewed as enhancing drug efficacy without evidence. Any dietary changes should be implemented as part of a comprehensive management plan that includes regular monitoring of glycaemic control, weight, and treatment response.

Patients taking insulin or sulfonylureas alongside GLP-1 therapy should monitor for hypoglycaemia when reducing sugar intake and seek medication review as needed. Those experiencing gastrointestinal side effects from GLP-1 therapy (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) should exercise caution with allulose, as additive effects on gut symptoms are theoretically possible.

Potential candidates who might consider incorporating allulose as part of their dietary strategy include individuals with type 2 diabetes or obesity who are seeking to reduce sugar intake whilst maintaining dietary satisfaction. Those following structured weight management programmes alongside GLP-1 therapy may find allulose useful as a tool for reducing overall caloric intake. However, emphasis should remain on evidence-based dietary patterns such as those recommended by NICE and Diabetes UK, which prioritise whole foods, fibre, and balanced macronutrient distribution.

Patients should contact their GP or diabetes specialist nurse if they experience unexpected changes in blood glucose control, significant gastrointestinal symptoms, or concerns about dietary modifications whilst on GLP-1 therapy. Persistent or severe vomiting or abdominal pain whilst on GLP-1 therapy may suggest pancreatitis and requires urgent medical attention. For pregnancy or breastfeeding, safety data for allulose are limited; individuals should seek clinician advice and follow any FSA condition-of-use restrictions. Suspected side effects of GLP-1 medicines should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Whilst preliminary research suggests allulose may modestly increase endogenous GLP-1 secretion, no clinical trials have demonstrated enhanced efficacy when combined with prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists. Allulose should be viewed as a dietary sugar substitute rather than a treatment enhancer.

Allulose is considered safe at FSA-authorised levels, though gastrointestinal side effects (bloating, diarrhoea) may occur and could be additive to GLP-1 therapy-related symptoms. Patients should start with small amounts and discuss dietary changes with their healthcare team.

No, there is currently no NICE, MHRA, or NHS guidance recommending allulose supplementation for patients receiving GLP-1 therapy. Dietary modifications should focus on evidence-based patterns recommended by NICE and Diabetes UK.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.