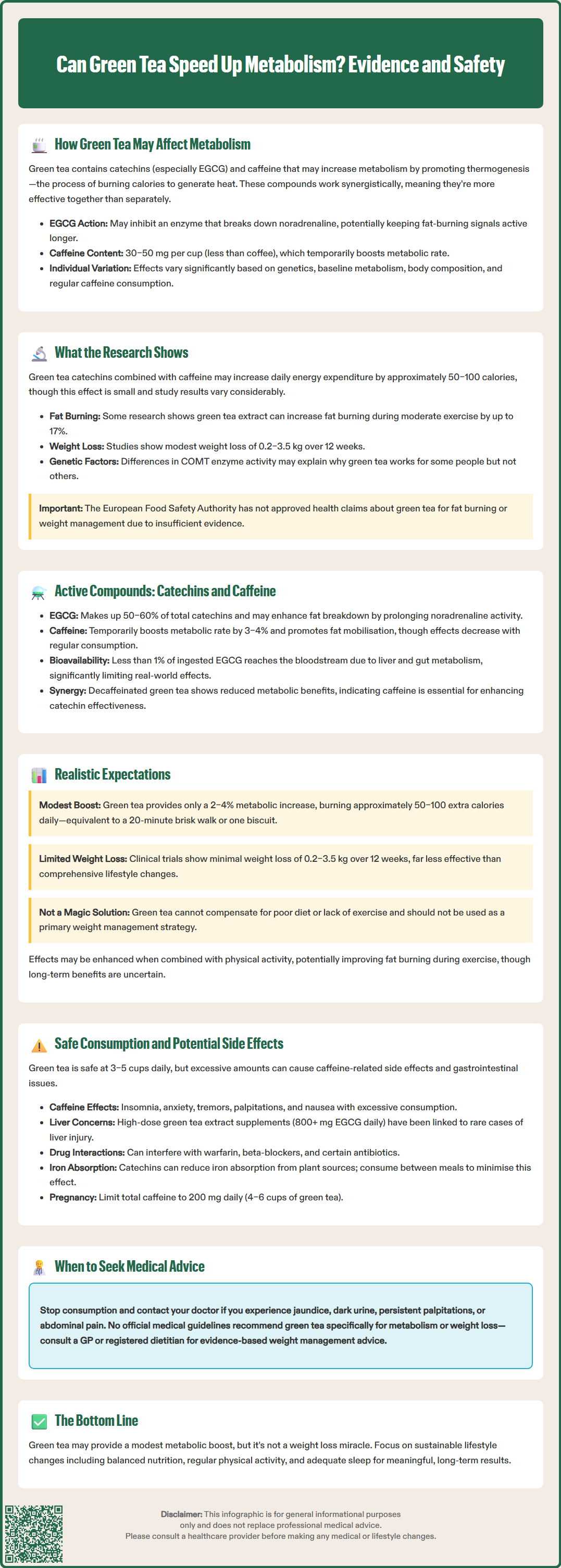

Can green tea speed up metabolism? This question has gained considerable attention as green tea (*Camellia sinensis*) becomes increasingly popular for its potential health benefits. The metabolic effects of green tea are primarily attributed to its bioactive compounds—catechins, particularly epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and caffeine. Research suggests these compounds may modestly increase energy expenditure and fat oxidation through thermogenesis, though effects vary considerably between individuals. Whilst some studies demonstrate small increases in metabolic rate, typically 50–100 kcal per day, the clinical significance remains uncertain. Understanding the evidence, mechanisms, and realistic expectations is essential for anyone considering green tea as part of a weight management strategy.

Quick Answer: Green tea may modestly increase metabolism by approximately 50–100 kcal per day through its catechins and caffeine content, though effects are small and vary considerably between individuals.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereGreen tea (Camellia sinensis) has been consumed for centuries and is increasingly studied for its potential metabolic effects. The question of whether green tea can genuinely speed up metabolism centres on its bioactive compounds, particularly catechins and caffeine, which may influence energy expenditure and fat oxidation.

Metabolic rate, or the speed at which the body burns calories, comprises basal metabolic rate (energy used at rest) and activity-related energy expenditure. Green tea's proposed mechanism involves thermogenesis—the process by which the body generates heat and burns calories. The catechins in green tea, especially epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), may enhance thermogenesis by potentially inhibiting an enzyme called catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), which breaks down noradrenaline. When noradrenaline levels remain elevated for longer, the sympathetic nervous system may signal fat cells to break down fat more efficiently, though this mechanism remains hypothetical in humans.

Additionally, the caffeine content in green tea—typically 30–50 mg per 200 ml cup compared to 60–90 mg in instant coffee and 90–140 mg in filter coffee—acts as a mild stimulant that can temporarily increase metabolic rate. Research suggests the combination of catechins and caffeine appears to work synergistically, potentially offering greater metabolic effects than either compound alone.

However, it is important to recognise that any metabolic increase is likely to be modest and variable between individuals. Factors such as genetics, baseline metabolic rate, body composition, and habitual caffeine intake all influence how someone responds to green tea. While the biological plausibility exists, the clinical significance of these effects requires careful examination of the evidence.

The scientific literature on green tea and metabolism includes numerous studies with varying methodologies and outcomes. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in the International Journal of Obesity have examined randomised controlled trials and found that green tea catechins, particularly when combined with caffeine, produced a small but statistically significant increase in energy expenditure—approximately 50–100 kcal per day on average, though results vary considerably.

Some research suggests that green tea extract may increase fat oxidation during moderate-intensity exercise. For example, Venables et al. (2008) found a 17% increase in fat oxidation during moderate-intensity exercise following green tea extract consumption, though these were short-term effects. Other trials have found no significant metabolic advantage. The heterogeneity in results may reflect differences in study design, dosage, duration, participant characteristics, and the specific green tea preparations used.

Important considerations include:

Genetic variation: Some research indicates that individuals with certain genetic polymorphisms affecting COMT enzyme activity may respond differently to green tea's metabolic effects, though these findings are preliminary and hypothesis-generating

Habituation: Regular caffeine consumers may experience diminished metabolic responses due to tolerance

Study duration: Short-term studies may show acute effects that do not translate into sustained metabolic changes or clinically meaningful weight loss

A Cochrane systematic review examining green tea for weight loss and maintenance (Jurgens et al.) concluded that whilst some evidence suggests modest weight loss (approximately 0.2–3.5 kg over 12 weeks), the clinical significance remains uncertain. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has not approved health claims linking green tea catechins to increased fat oxidation or weight management, citing insufficient evidence for a cause-and-effect relationship in the general population (EFSA NDA Panel, 2018).

Green tea contains a complex mixture of bioactive compounds, but the metabolic effects are primarily attributed to polyphenolic catechins and caffeine. Understanding these constituents helps explain both the potential benefits and limitations of green tea consumption.

Catechins are flavonoid antioxidants that constitute approximately 10–30% of green tea's dry weight, though brewed tea provides much lower doses than concentrated extracts. The four main catechins are:

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) – the most abundant and biologically active, comprising approximately 50–60% of total catechins

Epigallocatechin (EGC)

Epicatechin gallate (ECG)

Epicatechin (EC)

EGCG's proposed mechanism involves inhibiting COMT, thereby potentially prolonging noradrenaline activity in the sympathetic nervous system. This may enhance lipolysis (fat breakdown) and thermogenesis. Additionally, catechins may influence adipocyte (fat cell) differentiation and lipid metabolism at the cellular level, though these effects are primarily demonstrated in laboratory studies.

Caffeine content varies depending on brewing time, temperature, and tea variety, typically ranging from 30–50 mg per 200 ml cup in the UK. Caffeine acts as an adenosine receptor antagonist, increasing neural activity and stimulating the release of adrenaline. This can temporarily elevate metabolic rate by approximately 3–4% and enhance fat mobilisation from adipose tissue, though effects diminish with habitual consumption.

The synergistic effect between catechins and caffeine appears important. Studies comparing caffeinated versus decaffeinated green tea extract show diminished metabolic effects with decaffeinated versions, suggesting caffeine potentiates catechin activity. However, bioavailability of catechins is very low—often less than 1% of ingested EGCG reaches systemic circulation—which significantly limits their physiological impact. Extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver and gut substantially reduces the concentration of active compounds reaching target tissues.

Whilst green tea may offer modest metabolic benefits, it is essential to maintain realistic expectations based on current evidence. The metabolic increase associated with green tea consumption is relatively small—typically estimated at 2–4% elevation in energy expenditure, translating to approximately 50–100 additional kcal (calories) burned per day in most individuals.

To contextualise this effect, consider that a brisk 20-minute walk burns approximately 100 kcal, and reducing daily caloric intake by 100 kcal could be achieved by eliminating a single biscuit. Therefore, whilst green tea may contribute to energy balance, it cannot compensate for poor dietary habits or sedentary behaviour.

Key research findings include:

Weight loss attributed to green tea in clinical trials averages 0.2–3.5 kg over 12 weeks—modest compared to lifestyle interventions

Effects appear more pronounced in some studies with participants of Asian descent, possibly due to genetic differences in caffeine and catechin metabolism, though these findings are confounded by differences in habitual caffeine intake and other factors

Green tea may be more effective when combined with exercise, potentially enhancing fat oxidation during physical activity

Long-term sustainability of metabolic effects remains uncertain, with some evidence suggesting adaptation over time

It is crucial to recognise that green tea is not a substitute for evidence-based weight management strategies. NICE guidelines for obesity management (CG189) emphasise multicomponent interventions including dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural change. Green tea might serve as a complementary component within a comprehensive approach but should not be relied upon as a primary intervention.

Furthermore, there is no official link established between green tea consumption and clinically significant metabolic enhancement sufficient to recommend it specifically for weight management purposes. Individuals seeking metabolic support should consult their GP or a registered dietitian for personalised, evidence-based advice.

Green tea is generally considered safe when consumed in moderate amounts as a beverage, with most adults tolerating 3–5 cups daily without adverse effects. However, both the caffeine content and high doses of catechins—particularly in concentrated extracts—can cause side effects and interact with medications.

Common side effects associated with excessive green tea consumption include:

Caffeine-related effects: insomnia, anxiety, tremor, palpitations, and headaches

Gastrointestinal disturbance: nausea, abdominal discomfort, particularly when consumed on an empty stomach

Iron absorption interference: catechins can bind to non-haem iron, potentially contributing to iron deficiency anaemia in susceptible individuals

Hepatotoxicity concerns: The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued warnings regarding green tea extracts after reports of liver injury associated with high-dose catechin supplements. Whilst rare, cases of hepatotoxicity have been documented with concentrated extracts providing 800 mg or more of EGCG daily. Brewed green tea poses minimal hepatotoxic risk, but individuals with pre-existing liver conditions should exercise caution with supplements.

Drug interactions may occur with:

Anticoagulants (warfarin): Consistent intake of green tea is advised as very high volumes or matcha powder may affect vitamin K levels; patients should maintain consistent consumption and monitor INR as advised by their healthcare provider

Beta-blockers: Caffeine may counteract some effects of beta-blockers; green tea catechins may reduce absorption of certain medications like nadolol through OATP1A2 inhibition

Medications affected by CYP1A2: Caffeine levels may increase when taken with CYP1A2 inhibitors like ciprofloxacin or fluvoxamine

Other medications: Green tea may reduce absorption of certain drugs like fexofenadine through OATP1A2 inhibition

Safety recommendations:

Limit consumption to 3–5 cups of brewed green tea daily

Avoid high-dose catechin supplements unless under medical supervision

Pregnant women should limit caffeine intake to 200 mg daily (approximately 4–6 cups of green tea) as per NHS guidance

Individuals with cardiovascular conditions, anxiety disorders, or liver disease should consult their GP before significantly increasing green tea consumption

Take green tea between meals to minimise iron absorption interference

If you experience persistent gastrointestinal symptoms, palpitations, or signs of liver dysfunction (jaundice, dark urine, abdominal pain), discontinue use and contact your GP promptly. Suspected adverse reactions to green tea products can be reported through the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Research suggests green tea may increase energy expenditure by approximately 50–100 kcal per day on average, representing a 2–4% elevation in metabolic rate. However, effects vary considerably between individuals based on genetics, caffeine tolerance, and baseline metabolism.

Brewed green tea (3–5 cups daily) is generally safe for most adults. However, high-dose catechin supplements may cause liver injury and should only be used under medical supervision, particularly as the European Medicines Agency has issued warnings regarding hepatotoxicity with concentrated extracts.

No, green tea cannot substitute evidence-based weight management strategies. NICE guidelines emphasise multicomponent interventions including dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural change, with green tea serving only as a potential complementary component within a comprehensive approach.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.