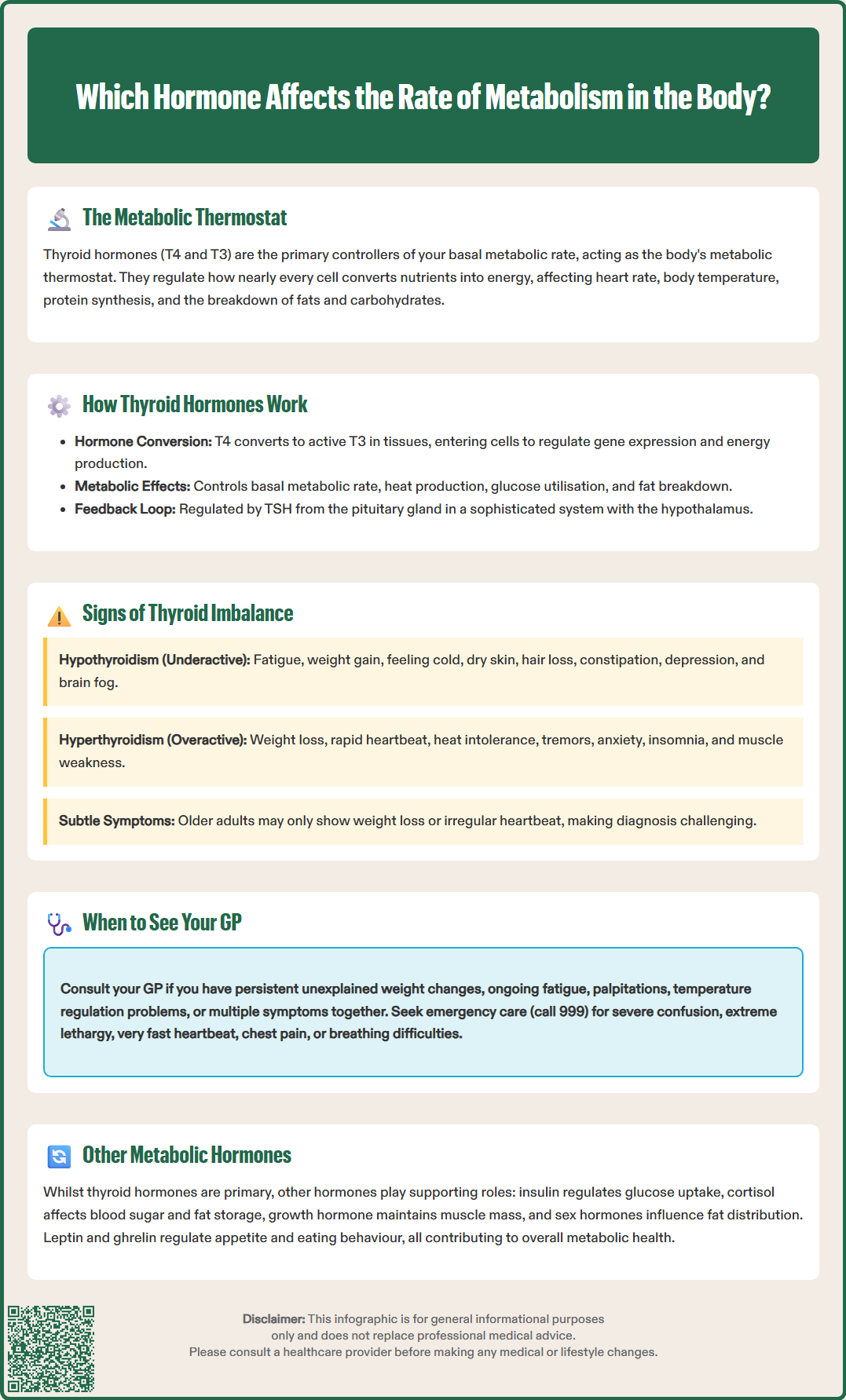

Thyroid hormones—specifically thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)—are the primary hormones that affect the rate of metabolism in the body. Produced by the thyroid gland, these hormones regulate how quickly cells convert nutrients into energy and control essential functions including heart rate, body temperature, and the breakdown of fats and carbohydrates. Whilst other hormones such as insulin, cortisol, and growth hormone contribute to metabolic processes, thyroid hormones serve as the body's metabolic thermostat. Understanding their function is crucial for recognising when metabolic imbalances occur, as both overactive and underactive thyroid conditions can significantly impact health, energy levels, and weight management.

Quick Answer: Thyroid hormones—thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)—are the primary hormones that control basal metabolic rate in the body.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereThe primary hormones that control basal metabolic rate in the body are thyroid hormones, specifically thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), produced by the thyroid gland in the neck. These hormones act as the body's metabolic thermostat, regulating how quickly cells convert nutrients into energy and how efficiently the body uses that energy for essential functions.

Thyroid hormones influence nearly every cell in the body, affecting processes such as heart rate, body temperature, protein synthesis, and the breakdown of fats and carbohydrates. When thyroid hormone levels are optimal, metabolism functions smoothly, maintaining a balance between energy production and consumption. The thyroid gland itself is regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from the pituitary gland, which responds to signals from the hypothalamus, creating a sophisticated feedback loop.

Whilst thyroid hormones are the principal regulators of basal metabolic rate, it is important to recognise that metabolism is influenced by multiple hormones working in concert. Insulin, cortisol, growth hormone, and sex hormones all play supporting roles in metabolic regulation. Additionally, the sympathetic nervous system and catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) contribute to acute changes in energy expenditure and thermogenesis.

Understanding thyroid hormone function is essential for recognising when metabolic processes may be disrupted. Both overproduction (hyperthyroidism) and underproduction (hypothyroidism) of thyroid hormones can significantly impact health, energy levels, and body weight, making thyroid assessment a cornerstone of metabolic evaluation in clinical practice.

Thyroid hormones exert their metabolic effects through complex cellular mechanisms. Once released into the bloodstream, T4 (the predominant form) is converted to the more active T3 in peripheral tissues, particularly the liver and kidneys. T3 then enters cells and binds to specific nuclear receptors, directly influencing gene expression and protein production. This process affects mitochondrial function—the powerhouses of cells—thereby controlling the rate at which cells produce energy from oxygen and nutrients.

The metabolic effects of thyroid hormones include:

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) regulation: Thyroid hormones determine the minimum energy expenditure required for vital functions at rest, including breathing, circulation, and cellular repair

Thermogenesis: They stimulate heat production, helping maintain normal body temperature

Carbohydrate metabolism: Thyroid hormones increase hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis) and enhance peripheral glucose utilisation by cells

Lipid metabolism: They promote the breakdown of fats (lipolysis) and reduce LDL cholesterol levels by increasing LDL receptor activity (hypothyroidism commonly causes hypercholesterolaemia)

Protein metabolism: In appropriate amounts, they support protein synthesis necessary for growth and tissue repair, though excess thyroid hormone can increase protein catabolism

The thyroid's activity is carefully controlled through a negative feedback system. When thyroid hormone levels drop, the hypothalamus releases thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which signals the pituitary gland to secrete TSH. TSH then stimulates the thyroid gland to produce more T4 and T3. Conversely, when thyroid hormone levels rise sufficiently, this feedback loop reduces TSH production, preventing excessive hormone release.

This intricate regulatory system ensures metabolic stability under normal circumstances. However, various factors—including autoimmune conditions, iodine deficiency, medications (such as amiodarone and lithium), and thyroid gland abnormalities—can disrupt this balance, leading to metabolic dysfunction that requires medical assessment and management. It's also worth noting that biotin supplements can interfere with thyroid function tests, so patients should inform healthcare providers about any supplements before testing.

Recognising the signs of thyroid hormone imbalance is crucial for timely diagnosis and treatment. Symptoms vary depending on whether the thyroid is underactive (hypothyroidism) or overactive (hyperthyroidism), though some presentations can be subtle, particularly in older adults.

Common signs of hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) include:

Persistent fatigue and low energy levels despite adequate rest

Unexplained weight gain or difficulty losing weight

Feeling cold, particularly in the hands and feet

Dry skin, brittle hair, and hair loss

Constipation and sluggish digestion

Low mood, depression, or cognitive difficulties ('brain fog')

Muscle weakness and joint pain

Heavy or irregular menstrual periods in women

Slowed heart rate

Signs of hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) include:

Unintentional weight loss despite normal or increased appetite

Rapid or irregular heartbeat (palpitations)

Feeling excessively warm or experiencing heat intolerance

Tremor, particularly in the hands

Anxiety, irritability, or nervousness

Difficulty sleeping (insomnia)

Increased bowel movements or diarrhoea

Muscle weakness, especially in the upper arms and thighs

Light or absent menstrual periods

Important red flags that require urgent medical attention include:

New or progressive neck swelling

Voice changes or hoarseness

Difficulty swallowing or breathing

Painful, red, or protruding eyes, double vision, or vision changes

It is important to note that these symptoms are non-specific and can occur in various other conditions. Additionally, older adults may present atypically, sometimes with weight loss and atrial fibrillation as the main features. Subclinical thyroid disorders may present with minimal or no symptoms whilst still affecting metabolic health. If you experience several of these symptoms persistently, particularly if they affect your daily functioning, it is advisable to consult your GP for appropriate evaluation, which typically includes thyroid function blood tests measuring TSH and free T4 levels. Testing is also recommended if you are pregnant, planning pregnancy, or have recently given birth and experience suggestive symptoms.

Whilst thyroid hormones are the primary regulators of basal metabolic rate, several other hormones significantly influence how the body processes and uses energy. Understanding this broader hormonal context provides a more complete picture of metabolic health.

Insulin, produced by the pancreas, plays a central role in glucose metabolism. It facilitates the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where it can be used for energy or stored as glycogen. Insulin resistance, where cells become less responsive to insulin, can lead to elevated blood glucose levels and is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes. This condition profoundly affects metabolic efficiency and is often associated with weight gain, particularly around the abdomen.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone produced by the adrenal glands, has complex metabolic effects. In appropriate amounts, cortisol helps regulate blood sugar levels and supports the body's stress response. However, chronically elevated cortisol—whether from prolonged stress, certain medications, or Cushing's syndrome—can increase blood glucose, promote fat storage (especially visceral fat), and break down muscle tissue, all of which negatively impact metabolic health.

Growth hormone, secreted by the pituitary gland, influences metabolism throughout life, not just during childhood growth. It promotes protein synthesis, stimulates fat breakdown (lipolysis), and helps maintain muscle mass. Growth hormone deficiency in adults can lead to increased body fat, reduced muscle mass, and decreased energy expenditure.

Sex hormones—oestrogen, progesterone, and testosterone—also affect metabolic processes. Oestrogen influences fat distribution and insulin sensitivity. The metabolic changes many women experience during menopause are multifactorial, with declining oestrogen levels contributing alongside other age-related changes. Similarly, low testosterone in men can reduce muscle mass and increase body fat, affecting overall metabolic rate.

Adrenaline and noradrenaline (catecholamines) and the sympathetic nervous system play important roles in acute metabolic regulation, particularly in thermogenesis and short-term energy expenditure during stress or exercise.

Leptin and ghrelin are hormones that regulate appetite and energy balance. Leptin, produced by fat cells, signals satiety, whilst ghrelin stimulates hunger. Imbalances in these hormones can affect eating behaviour and, consequently, metabolic health, though there is no official link establishing them as primary metabolic rate regulators in the same manner as thyroid hormones.

Knowing when to seek medical advice about potential metabolic or hormonal issues is important for maintaining health and preventing complications. You should arrange an appointment with your GP if you experience persistent symptoms suggestive of thyroid dysfunction, particularly if multiple symptoms are present or if they significantly affect your quality of life.

Specific situations warranting GP consultation include:

Unexplained weight changes: Significant weight loss or gain without clear dietary or activity changes

Persistent fatigue: Ongoing tiredness that does not improve with rest and affects daily activities

Cardiovascular symptoms: Palpitations, rapid heart rate, or chest discomfort, especially if accompanied by other metabolic symptoms

Mood changes: Persistent low mood, anxiety, or cognitive difficulties that are uncharacteristic for you

Temperature regulation issues: Persistent feeling of being too hot or too cold when others are comfortable

Menstrual irregularities: Significant changes in menstrual cycle pattern, particularly if accompanied by other symptoms

Family history: If you have close relatives with thyroid disorders, as some conditions have a genetic component

Pregnancy-related: If you are pregnant, planning pregnancy, or have recently given birth and experience symptoms of thyroid dysfunction

Neck changes: Any new or growing neck swelling, voice changes, or difficulty swallowing

Eye symptoms: Painful, red, or protruding eyes, double vision, or vision changes

Your GP will typically begin with a clinical assessment, including a physical examination of the thyroid gland (checking for enlargement or nodules) and blood tests. Standard thyroid function tests measure TSH initially, with free T4 if TSH is abnormal. Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies may be tested in suspected autoimmune thyroid disease or subclinical hypothyroidism. Free T3 is not routinely measured in primary care but may be tested in secondary care for suspected thyrotoxicosis.

According to NICE guidance (NG145), thyroid function testing should be considered in patients presenting with relevant symptoms, and treatment decisions should be based on both biochemical results and clinical presentation. If thyroid dysfunction is confirmed, your GP may initiate treatment or refer you to an endocrinologist for specialist management, depending on the severity and complexity of the condition.

Seek urgent medical attention if you experience severe symptoms such as significant confusion, extreme lethargy, very fast or irregular heartbeat, chest pain, or breathing difficulties. Call 999 or go to A&E for these emergency symptoms. For urgent but non-emergency concerns, contact NHS 111 for advice. For routine concerns, a standard GP appointment is appropriate and should be arranged without undue delay if symptoms persist beyond two to three weeks.

If you take supplements containing biotin (vitamin B7), inform your healthcare provider before thyroid testing, as biotin can interfere with test results. Similarly, mention any medications you're taking, particularly amiodarone or lithium, which can affect thyroid function.

Common symptoms of hypothyroidism include persistent fatigue, unexplained weight gain, feeling cold (particularly in hands and feet), dry skin, constipation, low mood or brain fog, and heavy or irregular periods in women. If you experience several of these symptoms persistently, consult your GP for thyroid function testing.

Thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) enter cells and bind to nuclear receptors, influencing gene expression and mitochondrial function. This controls how quickly cells produce energy from oxygen and nutrients, affecting basal metabolic rate, thermogenesis, and the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins throughout the body.

Consult your GP if you experience unexplained weight changes, persistent fatigue affecting daily activities, palpitations, significant mood changes, temperature regulation issues, menstrual irregularities, or any neck swelling. Your GP will typically arrange thyroid function blood tests measuring TSH and free T4 levels to assess thyroid health.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.