Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) affects millions in the UK, with obesity being the most significant modifiable risk factor. Ozempic (semaglutide), a GLP-1 receptor agonist licensed for type 2 diabetes, has gained attention for its weight-loss effects. Many patients wonder whether Ozempic might help with sleep apnoea alongside diabetes management. Whilst emerging evidence suggests weight loss from semaglutide may improve OSA symptoms, it is not licensed specifically for sleep apnoea treatment in the UK. This article examines the clinical evidence, explores the relationship between weight reduction and OSA, and outlines when to discuss treatment options with your GP.

Quick Answer: Ozempic may help improve sleep apnoea indirectly through significant weight loss, though it is not licensed in the UK specifically for OSA treatment.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

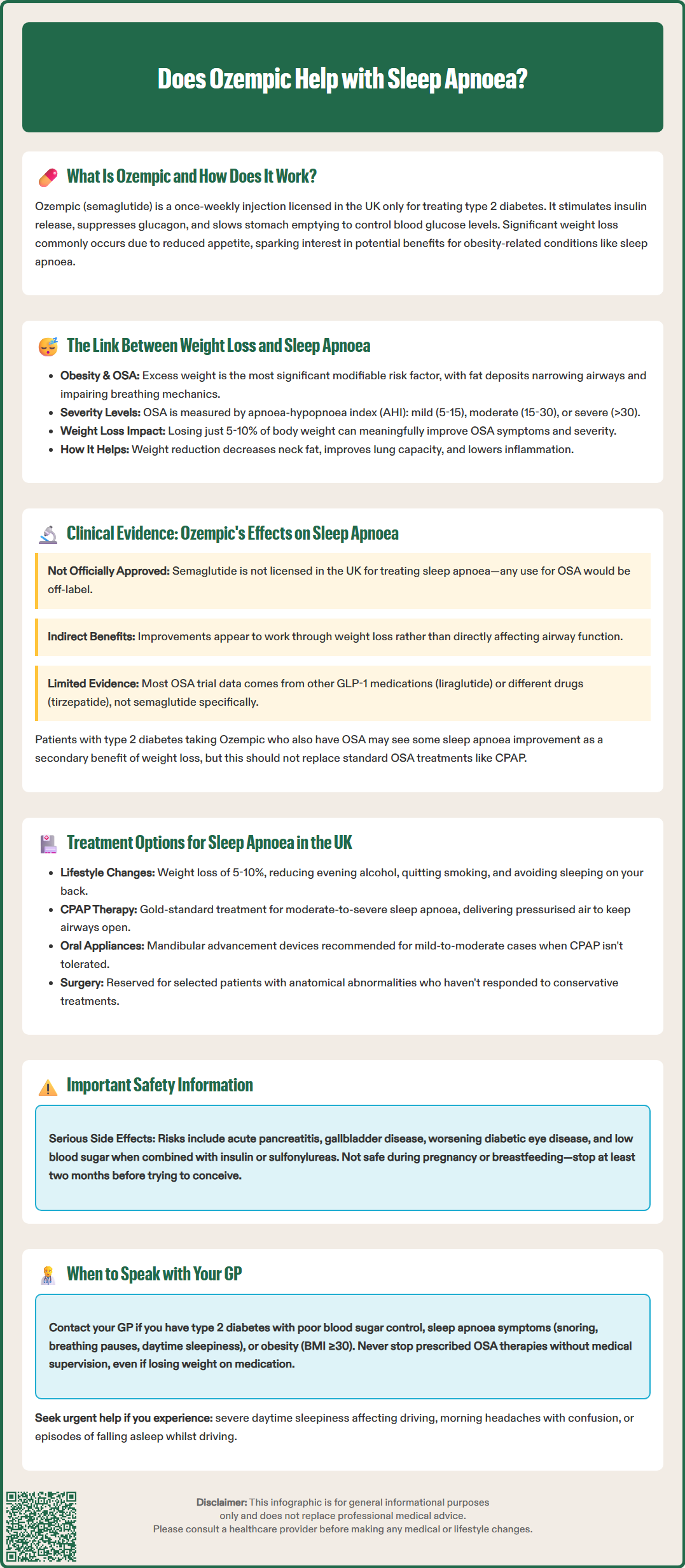

Start HereOzempic (semaglutide) is a prescription medicine licensed in the UK for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus only. It belongs to a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Ozempic is administered as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection and works by mimicking the action of the naturally occurring hormone GLP-1, which plays a crucial role in regulating blood glucose levels.

The mechanism of action involves several pathways. Ozempic stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, meaning it only promotes insulin release when blood sugar levels are elevated. Simultaneously, it suppresses the release of glucagon, a hormone that raises blood glucose. Beyond glycaemic control, semaglutide slows gastric emptying, which helps reduce post-meal blood sugar spikes and promotes a feeling of fullness.

A notable effect of Ozempic is weight reduction. Many patients experience significant weight loss during treatment, which occurs through reduced appetite and decreased caloric intake. This weight loss effect has generated considerable interest in the potential broader health benefits of semaglutide, including its possible impact on obesity-related conditions such as obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).

In the UK, Ozempic is regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and is available on NHS prescription for eligible patients with type 2 diabetes who meet specific criteria outlined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). It is important to note that whilst weight loss is a recognised effect, Ozempic is not currently licensed in the UK specifically for weight management in non-diabetic individuals—a separate formulation called Wegovy (also semaglutide, but at a higher 2.4mg dose) holds that indication.

Key safety considerations include risks of acute pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and potential worsening of diabetic retinopathy with rapid glycaemic improvement. Gastrointestinal side effects may lead to dehydration, and when used with insulin or sulfonylureas, there is an increased risk of hypoglycaemia. Ozempic is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding, is not indicated for type 1 diabetes, and should not be used to treat diabetic ketoacidosis.

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder characterised by repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to disrupted breathing, oxygen desaturation, and fragmented sleep. The condition affects a substantial proportion of the UK population, with obesity being the single most significant modifiable risk factor.

Excess body weight, particularly around the neck and upper body, contributes to OSA through several mechanisms. Adipose tissue deposits in the pharyngeal area can narrow the airway, whilst increased abdominal fat can reduce lung volumes and compromise respiratory mechanics. Additionally, systemic inflammation associated with obesity may contribute to airway oedema and collapsibility. Studies consistently demonstrate a dose-response relationship between body mass index (BMI) and OSA severity—higher BMI correlates with increased apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI), the primary measure of OSA severity. OSA is typically classified as mild (AHI 5-15), moderate (AHI 15-30), or severe (AHI >30).

Weight reduction has long been recognised as an effective intervention for OSA. NICE guidance acknowledges that even modest weight loss (5–10% of body weight) can lead to meaningful improvements in OSA symptoms and severity. More substantial weight loss often produces proportionally greater benefits, with some patients experiencing significant reduction in OSA severity, though it may not eliminate the need for other treatments such as CPAP in moderate to severe cases.

The mechanisms by which weight loss improves OSA include reduction of pharyngeal fat deposits, decreased neck circumference, improved lung volumes, and reduced systemic inflammation. These physiological changes translate into fewer apnoeic events, better oxygen saturation during sleep, reduced daytime sleepiness, and improved quality of life. Given this established relationship, any intervention that produces significant weight loss—including pharmacological treatments like GLP-1 receptor agonists—has theoretical potential to benefit patients with obesity-related OSA.

Some patients may have positional OSA, where symptoms are worse when sleeping on their back, and may benefit from positional therapy alongside weight management approaches.

The evidence for semaglutide's effects on obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is still emerging, and any potential benefits appear to be primarily mediated through weight loss rather than direct effects on airway physiology.

While robust clinical trial data exists for some medications in the broader GLP-1 receptor agonist class, the specific evidence for semaglutide in OSA is more limited. The SCALE Sleep Apnea trial investigated liraglutide (another GLP-1 receptor agonist) and found modest improvements in OSA severity associated with weight loss. Based on the established relationship between weight reduction and OSA improvement, it is reasonable to hypothesise that semaglutide-induced weight loss might similarly benefit OSA patients, though the magnitude of effect may vary.

Recent clinical trials with tirzepatide (a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist, not semaglutide) have shown significant improvements in OSA parameters, but these results should not be directly attributed to semaglutide as they involve a different medication with a distinct mechanism of action.

It is crucial to understand that there is no official indication for Ozempic specifically for sleep apnoea treatment in the UK. The MHRA has not licensed semaglutide for this purpose, and NICE has not issued guidance recommending GLP-1 receptor agonists as primary therapy for OSA. Any use of semaglutide for potential OSA benefits would be off-label unless the patient also has type 2 diabetes requiring treatment.

Further research is needed to establish the specific effects of semaglutide on OSA parameters, optimal patient selection criteria, and long-term efficacy. Healthcare professionals should interpret the available evidence within the context of each patient's overall clinical picture, including their diabetes status, BMI, and OSA severity.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who are prescribed Ozempic and who also have OSA may potentially experience improvements in their sleep apnoea as a secondary benefit of treatment-associated weight loss, but this should not be considered a replacement for established OSA therapies.

The NHS offers several evidence-based treatments for obstructive sleep apnoea, with the choice depending on severity, underlying causes, and individual patient factors. NICE provides comprehensive guidance on OSA management, emphasising a stepwise approach.

Lifestyle modifications form the foundation of OSA management for all patients. These include:

Weight loss through dietary changes and increased physical activity (target: 5–10% body weight reduction)

Alcohol reduction, particularly avoiding alcohol in the evening

Smoking cessation, as smoking increases airway inflammation

Sleep position training to avoid supine sleeping, which can worsen airway obstruction in positional OSA

Good sleep hygiene practices

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy remains the gold-standard treatment for moderate-to-severe OSA. NICE recommends CPAP for patients with moderate to severe OSA and for those with mild OSA who are symptomatic with affected quality of life. CPAP delivers pressurised air through a mask, keeping the airway open during sleep. Whilst highly effective, some patients find long-term CPAP use challenging due to discomfort, claustrophobia, or inconvenience.

Mandibular advancement devices (MADs) are custom-fitted oral appliances that hold the lower jaw forward, enlarging the airway space. NICE recommends MADs as an alternative for patients with mild-to-moderate OSA who cannot tolerate CPAP or prefer a different option.

Positional therapy devices may benefit patients with positional OSA, where breathing problems occur primarily when sleeping on their back.

Surgical interventions may be considered in selected cases, particularly when anatomical abnormalities contribute to obstruction. Options include uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), tonsillectomy, or maxillomandibular advancement surgery. However, surgery is typically reserved for patients who have failed conservative measures. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation is a specialist option with limited NHS availability for selected patients.

Recent developments include pharmacological approaches targeting weight loss, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, though these are not yet standard OSA therapy. Patients should discuss all available options with their GP or sleep specialist to develop an individualised treatment plan. Regular follow-up is essential to monitor treatment effectiveness and adjust management as needed.

If you have type 2 diabetes and suspected or diagnosed sleep apnoea, it is important to have an open conversation with your GP about whether Ozempic might be appropriate as part of your diabetes management. Several scenarios warrant discussion:

You should contact your GP if:

You have type 2 diabetes with inadequate glycaemic control despite other medications

You experience symptoms of sleep apnoea (loud snoring, witnessed breathing pauses, excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, difficulty concentrating)

You have obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) alongside diabetes and are struggling with weight management

Your current OSA treatment (such as CPAP) is not fully controlling symptoms

You are interested in exploring whether weight loss medication might benefit both your diabetes and sleep apnoea

Seek urgent medical advice if you experience:

Severe daytime sleepiness affecting daily activities or driving

Morning headaches with confusion or excessive tiredness (possible signs of obesity hypoventilation syndrome)

Episodes of falling asleep while driving

Your GP will assess your eligibility for Ozempic based on NICE criteria for type 2 diabetes management, which typically consider HbA1c levels, BMI, and previous treatments. They will review your complete medical history, current medications, and any risk factors requiring special consideration.

If sleep apnoea is suspected but not yet diagnosed, your GP may arrange a sleep study (polysomnography or home sleep apnoea testing) to confirm the diagnosis and assess severity. This is important because treatment decisions depend on accurate OSA classification.

Important safety considerations:

Whilst Ozempic may offer benefits for weight-related conditions including OSA, it is not a replacement for established OSA treatments like CPAP. Patients should not discontinue CPAP or other prescribed therapies without medical supervision. Common side effects of Ozempic include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and constipation, which typically improve over time. More serious potential side effects include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and worsening of diabetic retinopathy.

If you are planning pregnancy, Ozempic should be discontinued at least two months before a planned conception as it is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Effective contraception should be used while taking Ozempic.

Drivers with OSA have a legal duty to inform the DVLA if they experience excessive sleepiness that could affect driving. Follow DVLA guidance and discuss with your healthcare provider.

Report any suspected side effects to the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Your GP can provide personalised advice, coordinate care between diabetes and sleep services, and monitor your progress with regular follow-up appointments. A multidisciplinary approach—combining appropriate diabetes medication, weight management support, and evidence-based OSA treatment—offers the best outcomes for patients with both conditions.

No, Ozempic is not licensed by the MHRA specifically for sleep apnoea treatment. It is approved only for type 2 diabetes mellitus, though weight loss from treatment may secondarily benefit obesity-related OSA.

NICE guidance indicates that even modest weight loss of 5–10% of body weight can lead to meaningful improvements in OSA symptoms and severity, with greater weight reduction often producing proportionally larger benefits.

No, you should not discontinue CPAP or other prescribed OSA therapies without medical supervision. CPAP remains the gold-standard treatment for moderate-to-severe sleep apnoea, and any treatment changes must be discussed with your GP or sleep specialist.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.