Menopause brings significant metabolic changes that many women notice as weight gain, particularly around the abdomen, and difficulty maintaining previous body composition. Understanding how to speed up metabolism after menopause involves evidence-based strategies that preserve muscle mass, optimise energy expenditure, and support overall metabolic health. Whilst the decline in oestrogen affects fat distribution and insulin sensitivity, these changes are neither inevitable nor irreversible. This article explores the physiological mechanisms behind metabolic changes during menopause and provides practical, clinically supported approaches to maintain metabolic health through nutrition, exercise, and lifestyle modifications tailored to postmenopausal women.

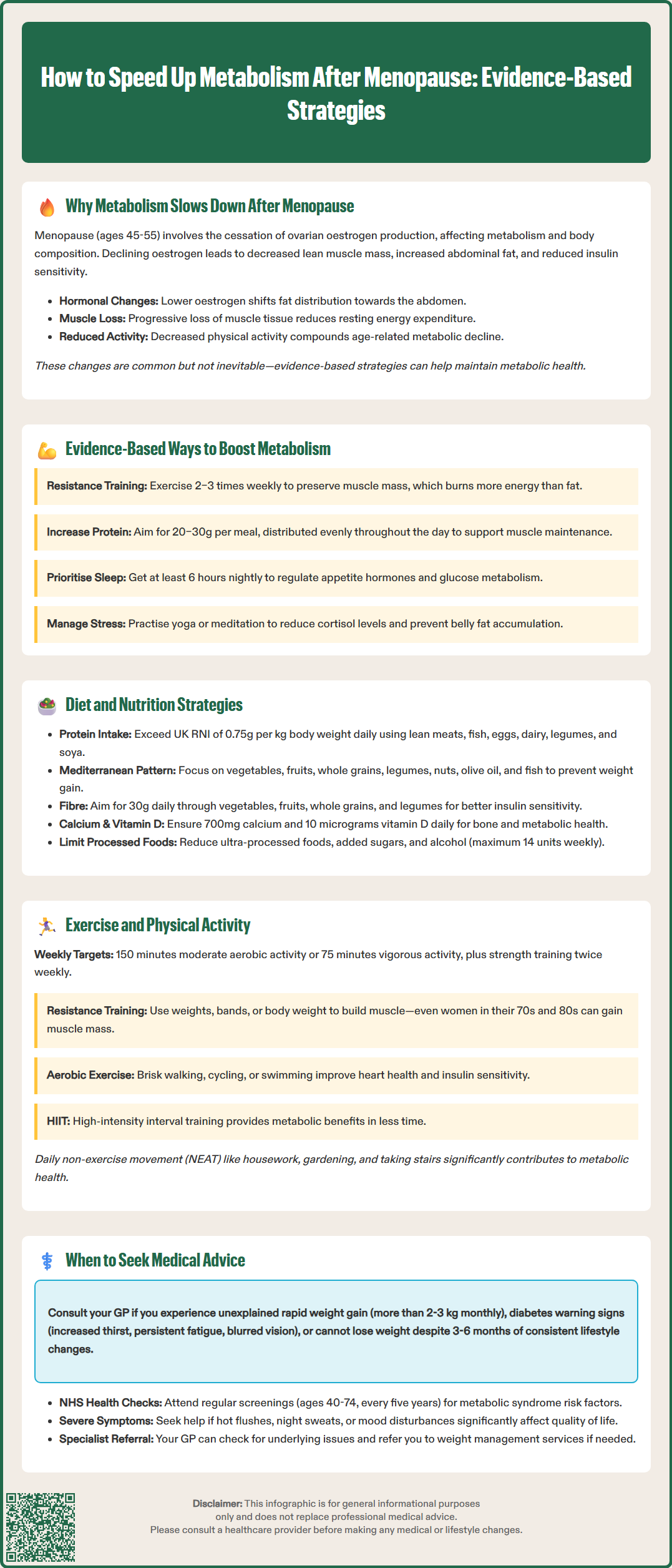

Quick Answer: Metabolism after menopause is best supported through resistance training 2–3 times weekly, adequate protein intake (distributed across meals), quality sleep, and stress management rather than quick fixes.

Mounjaro® is the most innovative GLP-1 medication proven to dramatically curb appetite, hunger, and cravings to help professional men achieve substantial weight loss.

Start Here

Wegovy® is a weekly injectable GLP-1 medication with proven effectiveness in reducing appetite, hunger, and cravings to help busy professionals lose significant weight.

Start HereMenopause, defined as 12 consecutive months without a menstrual period, typically occurs between ages 45 and 55. This transition marks a significant physiological change characterised by the cessation of ovarian oestrogen production, which affects metabolic rate, body composition, and energy expenditure.

The metabolic changes during menopause result from a combination of hormonal shifts and age-related factors. Oestrogen plays a role in regulating energy homeostasis, fat distribution, and insulin sensitivity, with receptors present throughout metabolic tissues including skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver. As oestrogen levels decline, several changes may occur: lean muscle mass tends to decrease, fat mass often increases—particularly around the abdomen—and insulin sensitivity may decrease.

Age-related factors compound these changes. Natural ageing is associated with a progressive loss of muscle tissue, reduced mitochondrial function, and often decreased physical activity levels. Research suggests that adults typically lose muscle mass with age, which contributes to a lower resting energy expenditure. The combination of hormonal and age-related changes creates conditions that can promote weight gain and altered fat distribution. Many women notice changes in body composition during the menopausal transition, with a tendency toward increased abdominal adiposity.

It is important to note that whilst these metabolic changes are common, they are not inevitable or irreversible. Understanding the underlying mechanisms empowers women to implement evidence-based strategies to maintain metabolic health during this life stage.

Whilst the term 'boosting metabolism' is often used in popular media, it is more accurate to discuss strategies that preserve metabolic rate and optimise energy expenditure after menopause. Evidence-based approaches focus on maintaining lean muscle mass, improving insulin sensitivity, and supporting overall metabolic health through lifestyle modifications.

Resistance training emerges as the most effective intervention for preserving and building muscle tissue. Research shows that progressive resistance exercise 2–3 times weekly can help maintain or increase lean body mass, which contributes to overall energy expenditure. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, requiring more energy at rest than fat tissue. The UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines (2019) recognise resistance training as a key component of healthy ageing for all adults.

Protein intake works synergistically with exercise to support muscle protein synthesis. While the UK Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) for protein is 0.75g/kg body weight daily, some research suggests postmenopausal women may benefit from slightly higher intakes to maintain muscle mass. Distributing protein intake evenly across meals (20–30g per meal) appears more effective than consuming most protein at one sitting. People with kidney disease should consult healthcare professionals before increasing protein intake.

Sleep quality significantly influences metabolic health. Poor sleep is associated with disruptions in hormones regulating appetite (ghrelin and leptin) and impaired glucose metabolism. Studies show associations between insufficient sleep (fewer than 6 hours nightly) and higher rates of weight gain and metabolic syndrome. Addressing menopausal sleep disturbances—whether through cognitive behavioural therapy, sleep hygiene, or medical management of night sweats—can support overall health.

Stress management is often overlooked but important. Chronic stress is associated with elevated cortisol levels, which may promote visceral fat accumulation and insulin resistance. Mind-body interventions such as yoga, meditation, or tai chi have shown benefits for both stress reduction and metabolic parameters in postmenopausal women.

Nutritional strategies for postmenopausal metabolic health extend beyond simple calorie restriction. A comprehensive approach addresses macronutrient composition, meal timing, and food quality to support insulin sensitivity, preserve lean mass, and promote sustainable weight management.

Adequate protein intake is foundational. As mentioned, while the UK RNI is 0.75g protein per kilogram of body weight daily, some research suggests slightly higher intakes distributed across three main meals may benefit muscle maintenance. High-quality protein sources include lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and soy foods. Soy products contain isoflavones (phytoestrogens) that may offer modest benefits for some menopausal symptoms, though evidence remains mixed and effects are generally small. Women with hormone-sensitive conditions should consult healthcare professionals before using isoflavone supplements.

Dietary patterns matter more than individual nutrients. The NHS Eatwell Guide provides practical, evidence-based guidance for balanced eating applicable to postmenopausal women. The Mediterranean dietary pattern—rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish—has robust evidence supporting metabolic health. Research suggests that adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns is associated with lower rates of weight gain and reduced cardiovascular risk.

Fibre intake supports metabolic health through multiple mechanisms: improving insulin sensitivity, promoting satiety, and supporting beneficial gut microbiota. The UK recommendation is 30g daily (SACN, 2015), yet most adults consume only 18–20g. Increasing consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes helps achieve this target whilst providing essential micronutrients.

Calcium and vitamin D warrant attention in postmenopausal women for both bone and metabolic health. Adequate calcium intake (700mg daily in the UK) from dairy or fortified alternatives, combined with vitamin D (10 micrograms/400 IU daily as recommended by UK health authorities), supports bone health. Between April and September, most people can obtain sufficient vitamin D from sunlight, but supplements are advised during autumn and winter months.

Limiting ultra-processed foods, added sugars, and alcohol is advisable. The UK low-risk drinking guidelines recommend not regularly exceeding 14 units of alcohol per week, spread over several days with drink-free days. Alcohol provides empty calories and may displace nutrient-dense foods in the diet.

Physical activity represents one of the most powerful tools for maintaining metabolic health after menopause. Current UK Chief Medical Officers' guidelines recommend that adults, including postmenopausal women, engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly, plus strength training on two or more days.

Resistance training is particularly crucial for postmenopausal women. Progressive resistance exercise—using weights, resistance bands, or body weight—stimulates muscle protein synthesis and helps preserve or build lean muscle mass. A well-designed programme should target all major muscle groups, progressively increasing resistance over time. Studies demonstrate that even women in their 70s and 80s can build muscle with appropriate training. Many community leisure centres and Age UK programmes offer supervised resistance training classes specifically designed for older adults.

Aerobic exercise supports cardiovascular health, improves insulin sensitivity, and contributes to energy expenditure. Moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or dancing—anything that raises heart rate and breathing but still allows conversation. High-intensity interval training (HIIT), involving short bursts of vigorous activity alternated with recovery periods, shows promise for improving metabolic markers in less time. However, HIIT should be introduced gradually, particularly for those who are deconditioned or have existing health conditions.

Daily movement beyond structured exercise matters significantly. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)—the energy expended in daily activities like housework, gardening, or taking stairs—can be substantial but varies widely between individuals. Reducing sedentary time by standing more, taking regular movement breaks, and incorporating activity into daily routines supports metabolic health.

Flexibility and balance exercises, whilst not directly affecting metabolism, reduce injury risk and support continued physical activity participation. Yoga, Pilates, and tai chi offer combined benefits of flexibility, balance, strength, and stress reduction.

Most people can safely start moderate physical activity without consulting a healthcare professional. However, those with cardiovascular, metabolic or musculoskeletal conditions may benefit from discussing exercise plans with their GP or a physiotherapist. Many NHS services offer exercise referral schemes providing supervised, tailored programmes.

Whilst metabolic changes after menopause are common, certain circumstances warrant medical evaluation to exclude underlying conditions or assess for complications requiring treatment.

Unexplained or rapid weight gain (more than 2–3 kg monthly) despite lifestyle efforts should prompt GP consultation. Whilst menopausal weight changes are typical, excessive or sudden changes may indicate thyroid dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, which becomes more common with age. Other potential causes include medication side effects (certain antidepressants, antipsychotics, or corticosteroids), Cushing's syndrome, or persistent metabolic features of polycystic ovary syndrome. Patients who suspect side effects from any medication should report these through the MHRA Yellow Card scheme.

Signs of type 2 diabetes require assessment. These include: increased thirst and urination, persistent fatigue, blurred vision, slow-healing wounds, or recurrent infections. NICE recommends using validated risk assessment tools (such as QDiabetes) for adults aged 40 and over (earlier in high-risk groups). Risk factors include age over 40, BMI ≥25 kg/m² (or ≥23 kg/m² in South Asian and some other ethnic groups), and family history. Diagnosis is confirmed with HbA1c or fasting plasma glucose testing.

Metabolic syndrome is typically asymptomatic but increases cardiovascular disease risk. It is characterised by central obesity, elevated blood pressure, abnormal lipids, and insulin resistance. Regular NHS Health Checks (offered to adults aged 40–74 every five years) help identify these risk factors early.

Severe menopausal symptoms affecting quality of life merit discussion with a healthcare professional. Vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats) disrupting sleep, mood disturbances, or significant weight changes may benefit from treatment. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), when appropriate, can improve some symptoms, though decisions must be individualised considering benefits and risks. HRT is not indicated specifically for weight management or metabolic disease prevention.

Difficulty losing weight despite sustained lifestyle changes over 3–6 months warrants review. A GP can assess for contributing factors, review medications, check thyroid function and other relevant blood tests, and potentially refer to specialist weight management services or dietitians. Some areas offer NHS-funded programmes like the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme for those at high risk.

Pre-existing conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or osteoporosis require ongoing medical supervision when implementing metabolic health strategies. Exercise programmes and dietary changes should be discussed with healthcare providers to ensure safety and appropriateness.

Metabolism slows after menopause due to declining oestrogen levels, which affect muscle mass, fat distribution, and insulin sensitivity, combined with age-related loss of muscle tissue and reduced mitochondrial function.

Resistance training 2–3 times weekly is most effective for preserving and building muscle mass, which maintains metabolic rate. This should be combined with 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly as recommended by UK guidelines.

Consult your GP if you experience unexplained rapid weight gain (more than 2–3 kg monthly), signs of diabetes (increased thirst, frequent urination, persistent fatigue), or difficulty losing weight despite sustained lifestyle changes over 3–6 months.

All medical content on this blog is created based on reputable, evidence-based sources and reviewed regularly for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep content up to date with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

DisclaimerThis content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional with any medical questions or concerns. Use of the information is at your own risk, and we are not responsible for any consequences resulting from its use.